|

|

|

| |

|

2013

May

28-31

|

How to make up a password that nobody can guess

When "hackers" break into a computer, it's usually by guessing a password.

They have computer programs that will try, automatically, all the words in the

dictionary (spelled forward or backward) and all the common number sequences

(especially numbers that are likely to be people's birth dates), as well as

locally popular slogans. They know about changing O, I, and E to 0, 1, and 3

to make a word look "hackish." So...

Here are some examples of bad passwords. Don't use them!

1968 GoDogs catlover p@ssword abc123 JohnBoy equanimity ytiminauqe

A good password needs to be:

- Relatively long. Three or four letters won't do it. Even ten aren't really enough.

- Not a word in any language, spelled forward or backward.

- Not visibly associated with you in any way — not your name, your uncle's name, your ZIP code,

your motto, your team's slogan...

Many computer systems require you to use characters other than letters. That at least keeps people

from using short words, but a series of unrelated words can be safer than a mixture of letters and digits.

As XKCD famously pointed out,

it takes tremendously more computing power to guess four unrelated words than to guess just one.

So that's one way to do it — make up a nonsense phrase.

Here's another, my preferred method. You need a 5-digit number, such as a ZIP code, but

not your own ZIP code, just one you happen to remember from somewhere.

Let's choose 02138, which is the ZIP code of Harvard University (I went to Yale).

You also need a sentence that is easy for you to remember, but is not a well-known

quotation. Let's use "This is my first attempt to make up an unguessable password."

Now: Your password is simply the number plus the initials of the sentence.

In this case, 02138Timfatmuaup. (Sorry about the "I'm fat" in there.)

You'll find that typing the initials of the sentence is surprisingly easy and quick.

It's safe to say that dictionary attacks won't work on this, and it's about as safe as

a password can be. (I'm not sure I agree with all of XKCD's calculations in the aforementioned

comic. In any case, the important thing about 02138Timfatmuaup is that it contains

nothing that could be guessed in advance.)

Now just make sure you're never tricked into typing your password into a fake login page

provided by a phisher, and you're all set.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

27

(Extra)

|

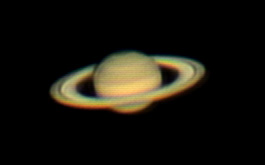

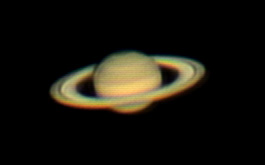

Saturn with a 5-inch telescope

I think this is a fairly respectable picture of Saturn considering that it was

taken with a small telescope (my old Celestron 5) under less-than-ideal conditions.

Using the telescope with a 3× Barlow lens, I took 4,157 frames of video

using my Canon 60Da in movie mode, then converted the .MOV file to .AVI with

VirtualDub, stacked all the frames with Registax 5 (which seems

to be more trustworthy for planetary work) and then did Gaussian deblurring with

Registax 6, followed by final editing in Photoshop.

The main thing this proves is that the Canon is sensitive enough to light that

it has no trouble imaging Saturn at f/30. My DMK and DFK cameras are right at

their limits in that situation. The Canon was set to 1/60 second and ISO 4000,

which is not the highest it will go.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

26-27

|

Memorial Day

Is it just my imagination, or is part of the "new economy" that businesses

are shutting down for Memorial Day more completely

than they used to?

Anyhow, just in case anyone imagines that it's National Barbecue Day, let me

refer you to what I wrote last year.

Honor those who risked their lives for you.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

25

|

How do we know what words mean in ancient languages?

With special reference to tetélestai in New Testament Greek

A correspondent asks how we find out the meanings of words in ancient languages,

particularly the original Greek of the New Testament.

This is the subject I'm professionally trained in — linguistics, with a bias

toward historical linguistics — so I'll attempt an answer.

I'm not going to do the research about my reader's question;

I'm just going to explain how it should be done.

My correspondent asks particularly about the word tetélestai (τετέλεσται),

usually translated "(it) (is/was/has been) finished."

We are being told it also could mean "paid in full," which, if true, would

support Augustian-Anselmian-Calvinist theology ("Jesus paid for your sins")

as opposed to, for instance, Eastern Orthodox theology, in which payment for

sins is only one of several metaphors that imperfectly describe what Jesus did.

tetélestai occurs in only two places in the

New Testament, John 19:28 and 30. Here's the ESV translation, with occurrences

of that word underlined.

After this, Jesus, knowing that all was now finished,

said (to fulfill the Scripture), “I thirst.”

A jar full of sour wine stood there, so they put a sponge full of the sour wine

on a hyssop branch and held it to his mouth.

When Jesus had received the sour wine, he said, “It is finished,”

and he bowed his head and gave up his spirit.

There is no doubt the word means something close to "finished."

New Testament Greek is not a lost language.

Koiné Greek is a late version of Classical Greek, the language of

Plato and Aristotle.

Greek never died out, and in the Greek Orthodox Church, people read the New Testament in the

original text today (although the language is not entirely like Modern Greek).

Over the years, there have been plenty of translations of the New Testament into other

languages, as well as discussions and explanations of the text

(by believers, heretics, and skeptics).

Also, tetélestai is (if you know Greek) an easily recognizable form

of the verb teleo, which definitely means "finish" or something close to it,

as in Matthew 10:23, "finish going through all the towns of Israel."

More generally, a good way to pin down the meaning of an ancient word is to

look for all the ways it is used, because then you know the meaning has to be

something that fits all of them (unless the word has multiple

separate meanings). If you look in a big ancient Greek lexicon,

this is exactly what you'll find — citations of one place after another

where the word was used by an ancient writer.

Even then, you have to ask whether it was the same kind of Greek.

If you find a word used in a surprising way, was it used by the same kind of Greek

speakers as the ones you're interested in? By analogy, suppose you found an

unusual word in my Daily Notebook, and the only other place you could find it was

a Shakespeare play. Would you assume that, 400 years later, I was using it the

same way as Shakespeare? It would be much more convincing if you found it in

a speech by John F. Kennedy; better yet if you found it in several early 21st-century

blogs.

So...

what are we to make of the claim that tetélestai meant, or could mean,

"paid in full"?

Sometimes, if we're lucky, we find someone — a philosopher, grammarian, or

religious thinker — who, in ancient times,

actually wrote an explanation of the meaning of a

word. This is how we understand the technical terminology of Stoic philosophy,

for example. But we don't have anything like this for tetélestai.

What we do have are reports that tetélestai was written on business

receipts that had been paid in full. Presumably, the classical scholar

or archeologist who discovered this published his discovery in a scholarly journal,

and a big Greek lexicon will give you a reference to where it was published.

Anyone making a thorough study of tetélestai should dig that up and check it out,

although, in fact, this kind of report is very unlikely to be inaccurate.

One would like to know whether the examples were from first-century Palestine, of course.

The next question is more subtle. Did tetélestai actually MEAN "paid

in full" when it was written on paid-in-full invoices? Or

did it just mean "finished" ("completed"), which would IMPLY payment

in full when written on an invoice? Do we have any record of anyone using the word in contexts where

it could ONLY mean "paid" and not "finished"?

I don't think anyone can conclude that tetélestai ONLY MEANT "paid in full"

— it's a form of a verb that clearly meant "finish" elsewhere.

At most we conclude that it COULD MEAN "paid in full" in some contexts,

and this would enrich the significance of what Jesus said on the cross.

But even that may be too strong. Maybe all we can conclude is that tetélestai was

ASSOCIATED WITH payment in full in some situations.

But, as I said, I haven't done the research — I've only been telling you how it

should be done. I would welcome further evidence.

One more thing. I forgot to mention the Aramaic factor.

On the cross, Jesus was almost certainly speaking Aramaic, not Greek.

This was also the everyday language of the disciples, who

spread the word in Greek later. We know that, on the cross, Jesus quoted

Psalm 22 in Aramaic, not Hebrew, which was surprising enough that the Aramaic

words got written down in Greek letters ("Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani").

So the question also arises what Aramaic word tetélestai would

render, and how much of the "paid in full" connotation would be applicable.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

23-24

|

Moved out

For the first time since 1984, I no longer have an office (other than at home).

On the afternoon of Friday, May 24, my nephews Aaron and Connor Paul brought their two

pickup trucks and moved my things out.

Then I took down my nameplate and turned in my key.

The spookiest thing was saying goodbye to the other people there and realizing that I

didn't need to tell the office manager when I'd be back. I'm not scheduld to be back.

Of course, I still have access to the electronics lab and to a desk in a shared office.

That is about to be painted and re-furnished, so I didn't put any of my things there.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

19-22

|

Happy granddaughter!

Lots of other activities are partly or completely on hold while we

enjoy a visit from Cathy, Nathaniel, and (last but not least) Mary,

who is making her first visit to Georgia.

Permanent link to this entry

End of an era

This is a sad picture — my office door stripped of all the pictures, with a

glimpse of the boxes stacked in the office, and plenty of wide-angle-lens distortion

to add to the air of unreality.

While cleaning out my desk (which I've had since 1984) I found a 1984 penny that

was still partly shiny. I'll post a photograph of it when it's unpacked.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

18

|

A fact of life: Grades matter

In the past couple of days I've had conversations with two graduate students

about an important fact of life: Grades matter.

The people who get C's in my courses don't get the same employment opportunities

as the people who get A's.

A Master of Science degree program is not a trade school where all you have

to do is pass the courses. Every successful graduate student is expected to

show real excellence in some specialty, as well as solid competence in everything

required for the degree.

I know everybody wants high grades. Not everybody earns them. As I've

already explained, my job is to grade all the students

by the same criteria. Errors are gladly corrected, but grades are not open to

negotiation. If they were, it wouldn't be fair to the students who don't

care to negotiate, or who got an A without haggling!

Permanent link to this entry

Buckling down to work

My consulting business is taking off like a rocket, and I have plenty of work

to do (thank goodness). I'm going to be less visible on line in the coming weeks.

Daily Notebook entries may be sparse, and I may be a bit slow responding to

non-essential e-mail. On Facebook, I may not even see every message targeted

at me — Facebook itself cuts back the notifications when there are too many.

I hope nobody feels I'm snubbing them!

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

15-17

|

Short notes

Spanish note: The Spanish word for "playpen" turns out to be "corralito"

(to corral the wild granddaughter!). (Guess who's coming for a visit?)

Packing: My books now fill 20 boxes in my office, and more boxes are on the way.

Paypal mishap: I was ordering boxes to be delivered to my office by Office Depot

(thus not having to cart them there myself). This worked fine a couple of weeks ago.

This time, though, I checked out through Paypal, and that caused Office Depot's computer

to pick up my Paypal delivery address (my home) rather than the delivery address I had

carefully typed in.

So they arrived — at my house — at 10:30 a.m. — while I was in the middle

of a Skype teleconference.

Fortunately, Office Depot is willing to pick them up, and deliver a new order of boxes

(not the same boxes!) to my office, and give me a small credit on the total cost.

Mishap averted: Melody and I were almost killed by a wrong-side-of-the-road driver

on Timothy Road this evening (May 17). He (she? it?) decided to pass a bicycle and several other cars,

in a no-passing zone, oblivious to oncoming traffic. All I could do was slow down and honk the horn.

I couldn't make my own car or the other oncoming traffic disappear.

This may be an instance of hillbilly driving. I've noticed that in mountainous areas, the local

drivers are accustomed to not being able to see very far ahead, and they seem to expect oncoming

traffic to stop and wait for them to go by. That is very foreign to me — I'm from South Georgia,

where the roads are straight.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

11-14

|

Down with Earthlink's spam protection!

Earlier today, an innocent and well-meaning gentleman up north asked me for

permission to reproduce something I had written.

It was one of my freely distributed handouts, so of course, I said yes.

But he didn't receive my answer.

Instead, Earthlink, his ISP, sent me an automatically generated message about

how to register with their spam protector so that I could send e-mail to their customer.

I thought this was mildly discourteous — after all, he was asking me a favor,

and I shouldn't have to jump through hoops. Why write to someone if you're not

going to accept the reply?

(But, as a technical point, I can accept that Earthlink may have been thrown off by

the fact that my actual "From:" address doesn't match my "Reply-To:" address. I use

an e-mail alias to shorten my address.)

Anyhow, the worst was yet to come. The Earthlink site kept showing me Captchas

(short sequences of letters, tilted and speckled) and then denying that I had typed

them correctly.

I was never able to register with Earthlink. I eventually just printed out the e-mail,

scrawled a reply, and sent it first class mail to the gentleman up north, who probably

has no idea Earthlink is doing this to his correspondents!

Permanent link to this entry

Good news at Micro Center, Duluth, Georgia

The Micro Center store in Duluth, Georgia, is converting its "gaming" section into a

robots-and-electronics section. They sell Arduino, Netduino, and Raspberry Pi systems

and parts. This is fortunate, because their competitor, Fry's, seems to be scaling back.

I'm glad to see hobby computing thriving again. I've seen several cycles.

In the 1980s, personal computers were fun to experiment with; in the 1990s and 2000s,

they were almost exclusively business machines; and now the fun is back, thanks to

low-cost ($35) gadgets that are as experimenter-friendly as the old Commodore 64,

and much more powerful.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

10

|

Falling cost of health care? YES...

Recently I predicted

that technological progress would lower the cost of health care,

and in particular, that we were about to see a drop in the cost of

prescription drugs as we got over a "bubble" of intense but expensive

research and development.

Well, Fox News reports

that it's really happening. American spending on prescription medicines fell last year, for

the first time in a while, and it's due to a new crop of low-cost generic drugs.

Meanwhile, two other developments in the business world are more disconcerting.

First, the same Fox report says that an automaker (I think they said GM)

may soon include advertisements

in the voice announcements from the car's computer.

Really bad idea. My car is my private property, not someone else's billboard.

Second, having already annoyed me with borderline sexual harassment,

Schlotzky's is now trying to be "edgy" with borderline racism — mock African-American language

on the employees' shirts. They've almost gotten rid of me already, and they must

be trying to finish the job.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

9

|

Why kidnapping-and-rape victims don't run away

(And a much-misunderstood point of sexual morality)

[Revised.]

I'll spare you the details of the Ohio kidnapping whose particulars are just

now hitting the news media. But you remember Elizabeth Smart, the Mormon girl

who was held captive in a similar way a while back. Here's what she has

to say:

| |

Rescued kidnapping victim Elizabeth Smart said Wednesday she understands why some human trafficking victims don't run.

Smart said she "felt so dirty and so filthy" after she was raped by her captor, and she understands why someone wouldn't run "because of that alone."

Smart spoke at a Johns Hopkins human trafficking forum, saying she was raised in a religious household and recalled a school teacher who spoke once about abstinence and compared sex to chewing gum.

"I thought, 'Oh, my gosh, I'm that chewed up piece of gum, nobody re-chews a piece of gum, you throw it away.' And that's how easy it is to feel like you know longer have worth, you know longer have value," Smart said. "Why would it even be worth screaming out? Why would it even make a difference if you are rescued? Your life still has no value."

— The Christian Science Monitor.

|

This is an important (if surprising)

psychological fact, and it explains a lot about kidnapping and human trafficking.

I also want to point out, very loudly, something else:

Christian sexual morality does NOT teach that rape victims are in any way "dirty," contemptible, or even guilty.

(Nor does Mormon morality, as far as I know. Ms. Smart is a Mormon, not a traditional Christian. I'm not aware

of any relevant differences.)

I think victims feel they are "dirty" for psychological reasons.

It is something we must oppose, counteract, and try to immunize them against.

Rape is common, and contempt (or, worse, self-contempt) for the victims compounds the damage.

In the specific case that Ms. Smart is talking about, she may have simply misunderstood her teacher.

(She was, after all, less than 14 years old at the time the misunderstanding happened.)

It sounds as if the teacher was talking

about how bad it is to make your own sexuality worthless by voluntarily devaluing it.

Being raped is nothing like that, and we need to say so, clearly.

But another thing that often happens is people who have an unhealthy contempt for sexuality think they are

upholding morality because they like limits on sexual behavior. They gain an audience as religious teachers.

But they like limits for the wrong reasons. Sometimes they are unduly focused on physical virginity rather than

moral character.

Morality puts a high value on human sexuality and wants to reserve it for worthy use.

Among sane people, there is controversy about what constitutes worthy use.

As a Christian, I believe it should be reserved for marriage, because only a lifelong commitment is enough

to justify total physical intimacy.

If you're on the other side of the Sexual Revolution, you disagree with me about this, but only

because you consider some other situations sufficiently worthy.

Not because you hate sexuality.

People who hate sex are not on either side of the controversy.

And the third thing I want to shout from the rooftops (although it doesn't pertain directly to the Ohio case

or the earlier mistreatment of Ms. Smart) is that human trafficking must end,

and furthermore, if you're a "sophisticated" person who thinks prostitution is a fine way to entertain people,

you're part of the problem. Look at the facts. Many prostitutes are slaves.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

8

|

Machine eats card

Yesterday (May 7; today, as I write this) was the last day of exams.

I wasn't involved, but I went to the office to do some computer administration

to pave the way for my successor (Dr. Fred Maier, our own alumnus;

congratulations, Fred!). Then I worked with my laptop in the library and

went to a vending machine for a snack...

I paid for my crackers using my UGAcard (which has a micropayment system

called Bulldog Bucks) and, with the UGAcard still in my hand, reached to pick

up the crackers. The card slipped through a crack and disappeared into the

depths of the machine.

Realizing the card might be in there for days or weeks, I went and got a replacement.

This cost $25 but only took half an hour, or less.

It also resulted in the lost card being deactivated — important so that

nobody can steal my Bulldog Bucks, enter various offices whose door locks use the card,

or take out library books in my name.

And if I ever need to scare away an attacker, all I have to do is make a face

like the picture on the card. I mean the picture of me, not the Georgia Bulldog!

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

7

|

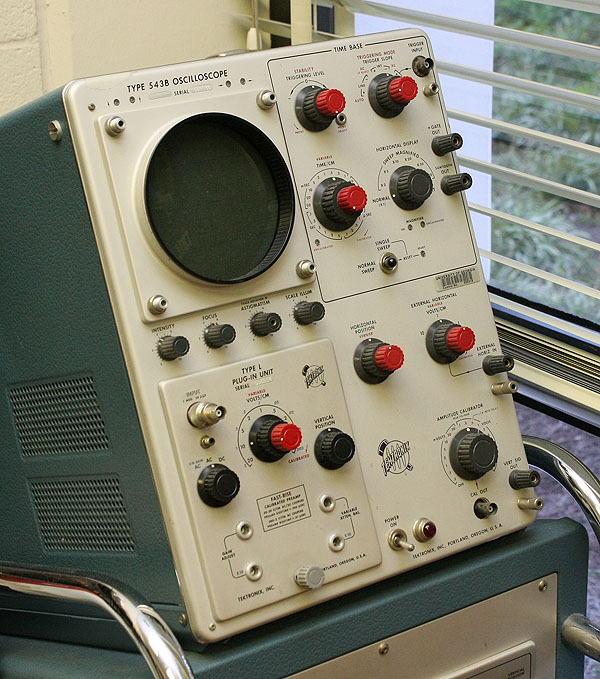

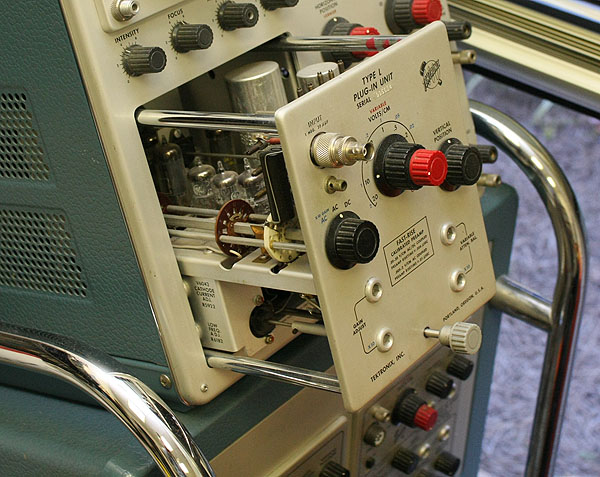

A vintage oscilloscope and other curiosities

Today (May 6) was the first day of actual removal of furniture from my office.

It happened as follows.

Two people from the University Libraries came to pick up a box of books I'm donating.

They saw my orange-and-yellow fabulous-1970s chairs, asked if we were getting rid of them, and laid

claim to them for the new offices they're moving into...

and then they saw my famous

concrete-embedded Fanta can

and claimed it, with cries of glee, for the University's archives.

At last I know it will have a good home.

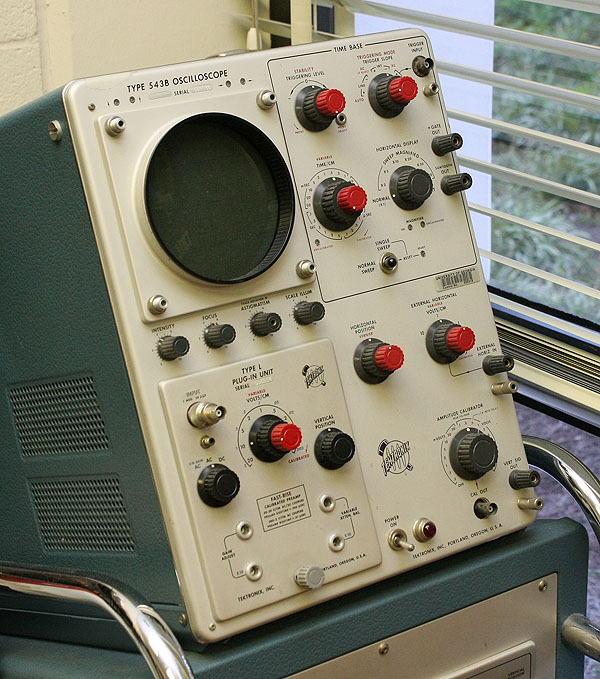

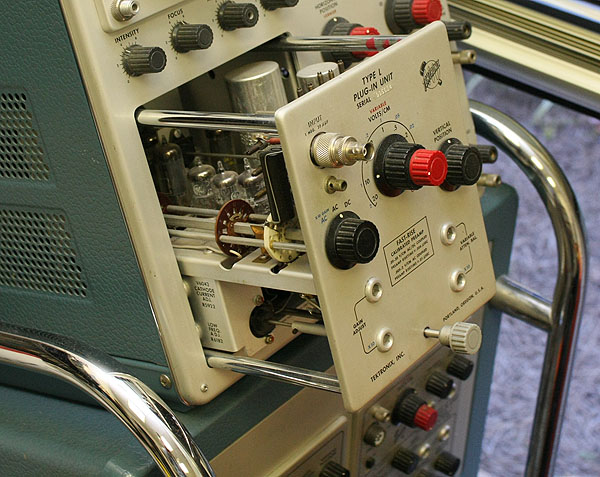

And then they saw the 50-year-old Tektronix 543B oscilloscope that has stood in my office

for about the last quarter century (and still works).

They were intrigued.

It has interchangeable amplifier modules.

It has plenty of vacuum tubes, but also (and this marks its place in history)

germanium transistors neatly arranged in sockets just like vacuum tubes.

Thanks to their visit, the old Tektronix oscilloscope is

probably going to become, literally,

a museum piece. Old Tektronix oscilloscopes are common, but they are rarely

in such good condition.

(Since this one is University property, I can't simply bring it home to use in

my home lab. Anyhow, I have better ones. My personal oscilloscope is a

Tektronix 2245, one of their last and best analog models; I also have a Tektronix

TDS 210A digital oscilloscope on indefinite loan from the manufacturer.)

Permanent link to this entry

Unseasonable end of term

I suppose someone might have said that it would be a cold day for the University

when I finally stopped working here...

and it's shaping up to be. This week we are having rain, with temperatures in

the mid-50s F. That is abnormally cold for May in Georgia.

Eighties would be more typical. Have they given us the weather for Edinburgh

by mistake?

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

6

|

Bitcoin: should we trust it?

Bitcoin is a new Internet-based medium of exchange

that people are using as an alternative to government-issued money.

What are we to make of it?

First, let me make it clear that Bitcoin is not a get-rich-quick scheme, pyramid, or source

of free money, although some speculators seem to have viewed it as all of these things.

It is just a medium of exchange, something you can receive and spend instead of dollars or euros.

The system is called Bitcoin and the units of currency are called bitcoins.

Bitcoins are not physical objects; they are digital codes, although a few people have made

coins or "banknotes" with the digital codes printed on them.

The Bitcoin system relies on digital signatures (public-key encryption). I'll explain the math

some other time. The key idea is that, using a digital signature, you can do something to a digital code that no

one else can do, and everyone else can prove that it was you who did it, even though they can't do it

themselves. Digital signatures are much more secure than signatures penned on paper.

To own bitcoins, you have to have a Bitcoin address. This is essentially an account — except

that you don't have to identify yourself in order to get one. You just have to request an address code and

password, and hang on to them. If you lose your password, all your bitcoins are lost forever.

Every Bitcoin transaction is recorded in the Bitcoin database. This doesn't violate your privacy because

you never had to identify yourself in the first place. What it accomplishes is to prove who owns every

bitcoin at every moment. If you try to spend the same bitcoin twice, the database will catch you.

Full checking of a transaction takes ten minutes to an hour, and in high-risk situations, people are

advised to allow this amount of time to confirm a payment.

The Bitcoin system relies on a huge distributed network of volunteers with computers, maintaining

the database and doing calculations to support it. This kind of volunteering is called bitcoin mining

because you're paid for it — more precisely, you're given some newly generated bitcoins of your own.

That's how bitcoins enter circulation. Eventually, this kind of payment will stop, and the world's supply

of bitcoins will stop. This mechanism is built into the Bitcoin algorithms.

Now then. Should we trust Bitcoin?

Let me begin by saying that I would support privately-issued commodity-based currency, maintained by a

responsible banking organization. I also am sure that Bitcoin's

technology can play a large role in the currency of the future.

But Bitcoin's currency is not commodity-based.

Nor is it "fiat money," declared to be legal tender by some government (like dollars, pounds, or euros).

It's something worse.

Bitcoins are not redeemable in any way and are not backed by the faith and credit of any entity public or private,

not even a corporation.

They get their value only from people's confidence in them.

My second concern is the security of the Bitcoin system. It's newly invented, which means people

haven't figured out how to compromise it yet. That doesn't mean they're never going to.

My impression of the Bitcoin crowd is that they have too much confidence in the cleverness of their

new invention. Something unforeseen is sure to go wrong eventually.

The biggest vulnerabilities might be

from low-tech tactics, such as tricking people into giving away their passwords,

or manipulating the market with false news.

My third concern is that Bitcoin is alleged to be very popular with the underworld.

This may be only an allegation, and there is nothing intrinsically evil about letting people make

and receive payments anonymously. (That's what coins and paper money were for, in the first place!)

But if Bitcoin ends up being popular with drug cartels or terrorists, that would give a lot of

civilized people an incentive to bring it down suddenly, causing innocent individuals to lose

all their money. Even small moves to take down Bitcoin would undermine confidence in it,

greatly reducing the value of bitcoins in the marketplace.

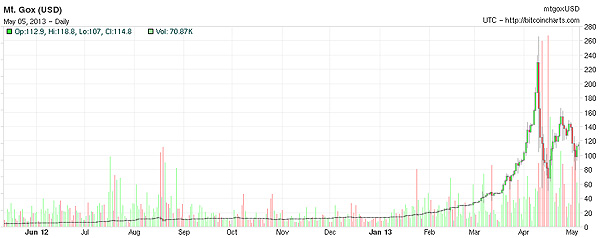

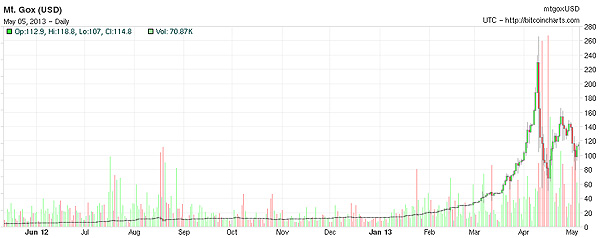

Finally, my fourth concern is the bubble-like behavior of the value of bitcoins.

Below, you see the free-market exchange rate between bitcoins and U.S. dollars.

(The dollar was quite stable during this time.) Through 2012, the bitcoin gradually rose

from about $10 to $20, exactly as one might expect as people gained confidence in it.

But then what happened? We had a spike to about $230, a crash, and some further wild

fluctuations. At best, for a while, bitcoins were a speculative investment. They're not

something in which I'd like to store value now.

So if the goal of Bitcoin was to create a stable medium of exchange, we can't say it has succeeded.

[Addendum:] A friend asks the obvious question, Why would anyone use Bitcoin in the first place?

Two reasons: it's a fashionable thing on the Internet (and that's enough to make it compulsory for a

certain sort of person), and more importantly, it provides the convenience of the Internet combined

with complete anonymity. Other funds-transfer services, such as Paypal or anything run by a bank,

require you to identify yourself.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

5

|

How not to define a word

When you define a word, you have to use words that the hearer already understands,

not more new terms you just made up. If you do the latter, you're not explaining anything.

Let me give an example. Some time soon, I'm going to write about Bitcoin, which is a

newly invented medium of exchange.

Most definitions of Bitcoin start out, "Bitcoin is a virtual currency..."

Bzzzzt! Wrong! "Virtual currency" is a new term made up by, as far as I can tell,

the same people who invented Bitcoin. It is not something we were familiar with beforehand.

The only people who know what it means are people who already know about Bitcoin.

By contrast, I had the good sense to tell you Bitcoin is a medium of exchange.

I haven't told you a thing about how Bitcoin works (in fact it's massively complicated),

but at least I've given you something that is true and understandable, rather than a new term to wonder about.

Closely related is the widespread Microsoft practice of "defining" words with

marketing superlatives rather than with definitions.

For example, it took me an unduly long time to find out what Silverlight is.

It is essentially a multiplatform runtime engine for using C# and related programming languages

within web browsers, to compete with Java. But Microsoft marketers won't tell you that.

They'll only tell you that it's "a powerful development tool for creating engaging,

interactive user experiences for Web and mobile applications."

Those are their exact words, copied from a web site, and they could hardly do a better

job of not telling me what Silverlight is. I already knew it had something to

do with software development, and beyond that, they're not saying anything.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

4

|

After 30 years of teaching

[Minor updates May 19.]

I've graded my last student projects and turned in the grades.

Here, now, are a few reflections on what all these years of teaching

— nearly all of it postgraduate — have been like.

The first thing on my mind is grade appeals. When a student isn't happy

with his or her grade, what do I do?

Well, first I insist that the student point out a specific error or

inequity in the grading. Simply wanting more points is not grounds for

an appeal. I am glad to correct any actual mistake, of course, but I don't

negotiate grades as if they were the price of a used car.

A grade is an expert judgment of the student's mastery of the material.

If you negotiate an expert judgment, all you do is make it inaccurate,

and it's not fair to the student who didn't try to negotiate.

Second, I require that the appeal be made in writing, and then I take

at least 24 hours. I never make a correction instantly, no matter how

clearly it is warranted. There might be other factors to be taken

into account. A related query might come in from another student.

My overall philosophy of grading is summarized here.

(Click through and read it.) Crucially, grades are a system of communication

and I feel duty-bound to use them the same way others do; I'm not free to make up

my own peculiar system. Moreover, I don't grade on a curve because doing so would

not be statistically valid unless I had hundreds of students. Fairness, as Plato said,

requires treating like cases alike, and I don't want a student's grade to be influenced

by the performance of other students who happen to be in the class at the time.

Teaching in graduate school has specific challenges.

Our degree program is a Master of Science in Artificial Intelligence.

With some students, the challenge is simply getting them to aim high enough.

You're not here just to get some technical training.

You're here to become a scientist (that's what "Master of Science" means)

and take responsibility for the quality of your own work (not just get

through our exams; that's what professionalism means).

I often tell students that if your papers look like they are "student work," they're

not good enough. Student work was for when you were an undergraduate.

When you get here, you already have a degree and are expected to act like it.

The teacher is your colleague, not your adversary.

A corollary to this is that, at the master's degree level,

I don't provide much of a safety net to keep

people from failing. I've learned that it's counterproductive. If a student starts

thinking that it's my job to come and challenge him whenever he starts

neglecting something, he's not taking responsibility for his own achievements.

I don't play that game. Of course, I give encouragement generously when people do

good work, even if there are flaws in it.

Important point: We have plenty of excellent students who take the

initiative and do excellent work. Most of what I'm saying here applies only to

a few of the weakest — but a surprising amount of a teacher's effort goes

toward those.

For the weaker students, a particular challenge is writing. Real scientists have to write papers

all the time, and a real scientist can write a paper with every word spelled right,

every sentence correctly punctuated, and (most importantly!) all the

ideas arranged and explained so that other people can understand them.

This is not a task for some other class of highly-educated people. In graduate school,

you are a highly-educated person. If not now, when?

Ninth-grade English will not be re-taught in graduate school.

Instead, you have to take responsibility for your own skill set and fill in gaps

on your own.

If I had it to do again, a month before the end of the term, I would give a test on

readiness to write a term paper.

The purpose is to send the message that this is required knowledge.

It would include such things as correcting the

spelling and grammar errors in a short passage; writing a bibliography entry in a standard format; and (crucially)

saying how you decide what should and should not be listed in a bibliography.

(Hint #1: The bibliography lists only the things you cite in the paper; it is not a list of everything you read.

Hint #2: Software does need to be cited, not just books and journals.

Hint #3: Textbooks and encyclopedias that give you "common knowledge" — information

available from many sources — do not need to be cited or listed. Cite only sources of

unique ideas or information.)

Two thirds of the class would breeze through this test, and the

remaining third would be aware of what they need to strengthen.

I think our educational system does some people a disservice by making "English" a subject

separate from science, mathematics, and the like. It gives some people an excuse not to

learn how to write. They don't see their role models (in science or business) doing it;

they think it's only for little old ladies who spend all their time reading poetry.

But in science, if you can't write, you might as well not be doing

anything else — written reports of research are our end product!

Permanent link to this entry

A time of subtraction

The sad thing about this time in my life — retirement and the transition to consulting —

is that I'm giving up activities and possessions and not acquiring new ones.

Leaving my generous-sized UGA office, I have to downsize, and my home office was already overfull.

What's more, electronic equipment doesn't hold up when you neglect it for twenty years —

my circa-1995 stereo in my office seems to be unwanted now, and the cassette deck is giving some

trouble, so I don't know how to find it a new home. Then there's my rapidly decaying home electronics shop...

Just like my office, my schedule has also been overfull for a long time;

all the new activities started some time ago, so there's nothing much to add now.

I've been extremely busy for over twelve years — since starting a schizophrenia research

project with GSK in 2000 — and it will be a relief to drop back down to just working full-time.

Whether anything really new will come along, I don't know. I want to caution everyone that

I'm not a man of leisure and am not really looking for ways to fill up the idle hours!

Permanent link to this entry

Short notes

It's bad enough when people cross the street with their cell phone to their ear and their head down,

not looking at the cars. Now the Google Glass is coming, an excuse not to look at anything.

I remember the summer of 1981, when the Sony Walkman burst on the scene and, for the first time,

people were walking around in public with headphones on.

A youth group of some sort (athletic, I think) was visiting Yale, and its Walkman-wearing members

would try to go through dining hall lines with the headphones on.

"Huh?" "What did you say?" We laughed. They didn't hear us laugh.

In other news, Campus Crusade for Christ is now known as "Cru." I'm glad they dropped "crusade"

because the Crusades were not altogether a proud moment in history.

But maybe their new name is too concise. It sounds like a rowing team.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

2-3

|

An economic note

Something I am starting to observe in the business world is that

positions are going unfilled because employers aren't offering adequate

salaries. Everybody's stuck thinking we're still in a deep recession and

good workers ought to work for peanuts.

I can't give any specifics because of confidentiality, but I invite you

to look for evidence that this is going on.

National unemployment is now 7.5%. That is higher than we'd like, but

it's getting closer to normal. Remember, normal is about 4.5%, not zero.

At any given time, some people are changing jobs or holding out for a better offer.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2013

May

1

|

Is there life outside academia?

I am on the verge of being outside of academia for the first time since

kindergarten started in September of 1962, more than half a century ago.

Ever since then, I have been either a student or an employee of an

educational institution. Not any more. Years will no longer ebb and

flow every September and June. One month will be like another, except

for the weather.

My retirement and change of career are at hand — heralded by

a redecoration of the Daily Notebook. I had originally planned to roll out

the "new look" on June 1, which is the official retirement date, but it has

become increasingly evident that the real changes are happening sooner.

My last day of active employment is May 10, but in fact May 1 is the first

day that I don't actually have to come to campus — there is nothing

scheduled for that day. I do have to come in later this month

to grade student projects, handle any administrative responsibilities, and

move out of my office.

What does it feel like? Hard to say. I plan to continue hanging around the

campus, using libraries, going to seminars, and so forth; I'm not gone.

But I think that fundamentally, academia is not the only place I can thrive.

People ask me if I'll miss teaching. As I observed the other day, teaching is

actually not my first love among scholarly activities. That is writing.

The other things you can't stop me from doing — either as a hobby or as

a profession — are photography and technological problem-solving.

I am happy to have been able to do a good bit of all three of these while earning

my living. May it continue.

During the first half of my life, or more, I was, like most people, not sufficiently aware of

the amount of serious intellectual activity that goes on in business and industry.

I knew I was going to be a Ph.D. from the moment I learned what such a thing was,

and I always assumed college teaching would be a large part of my career;

that's what scholars do, isn't it?

I must, however, thank my Aunt Dorothy (Miller), who, when I was about eight years

old, pointed out the difference between a "scientist" (in government or industry)

and a "professor of science" (in academia). I've vacillated between the two roles,

but I'm grateful for having had at least some awareness of the distinction from

an early stage.

I should add that I am not the kind of scholar who has managed to meld everything I am

interested in into a single career. Scholars in fields like literature or philosophy often manage

to do this (think of C. S. Lewis). My profession is too specialized and my interests are

too wide; there's no way everything I'm interested in can fit into a single profession.

I'm aiming to be a Ben Franklin, not an Einstein.

(I once said that to a noted historian, who immediately opined that Franklin was considerably

the greater scientist of the two. Was he? I hardly know, and that wasn't what I had in mind.

If Einstein had not had his

insights, would other physicists soon have covered the same ground? I simply don't know.

Franklin gave us at least

one major scientific breakthrough — the distinction between positive and

negative electricity — in the middle of a career as a diplomat, statesman, writer, and who

knows what else!)

Important note: In the months and years to come,

although I won't be working quite as hard, I will

be working. Clients are already waiting for me to start projects.

And I generally can't tell you what I'm working on — it has to do with

unannounced products. When I don't say what I'm doing, that doesn't mean I'm

not doing anything!

Permanent link to this entry

|

|

|

This is a private web page,

not hosted or sponsored by the University of Georgia.

Copyright 2013 Michael A. Covington.

Caching by search engines is permitted.

To go to the latest entry every day, bookmark

http://www.covingtoninnovations.com/michael/blog/Default.asp

and if you get the previous month, tell your browser to refresh.

Entries are most often uploaded around 0000 UT on the date given, which is the previous

evening in the United States. When I'm busy, entries are generally shorter and are

uploaded as much as a whole day in advance.

Minor corrections are often uploaded the following day. If you see a minor error,

please look again a day later to see if it has been corrected.

In compliance with U.S. FTC guidelines,

I am glad to point out that unless explicitly

indicated, I do not receive substantial payments, free merchandise, or other remuneration

for reviewing or mentioning products on this web site.

Any remuneration valued at more than about $10 will always be mentioned here,

and in any case my writing about products and dealers is always truthful.

I have a Tektronix

TDS 210A oscilloscope on long-term loan from the manufacturer. Other reviewed

products are usually things I purchased for my own use, or occasionally items

lent to me briefly by manufacturers and described as such.

I am an Amazon Associate, and almost all of my links to Amazon.com pay me a commission

if you make a purchase. This of course does not determine which items I recommend, since

I can get a commission on anything they sell.

|

|