|

|

|

|

|

If your browser labels this site "Not Secure," click here.

|

|

2018

September

28

|

Grading on a scale from 50 to 100

[Revised.]

Some elementary schools now grade on a scale from 50 or 60 to 100, with no grades

below 50 or 60. If you don't turn in your homework at all, you score 50 or 60 on it,

instead of the traditional 0.

My first reaction was that this is nonsense. If a missing paper isn't 0 points, what is?

But then I thought about it and realized what they're going for.

The difference between 60 (a minimum passing paper, turned in) and 0 (no paper turned in)

is simply too much. You don't want to say that a missing paper is 2.5 times as bad

(that is, 2.5 times as far from 100) as one at the bottom of the passing range.

Or to put it another way, if a missing paper scores 0 but a barely passing paper scores 60,

you're giving too much reward for barely passing work.

From the student's point of view, a missing paper shouldn't hurt your grade much more

than a very badly done one. Missing a paper does not deserve a special, terrible penalty.

And that's the reason for clamping the bottom of the scale at 50 or 60 instead of 0.

Why not rework the whole scale so that a missing paper is 0, a failing paper is close

to 0, and a perfect paper is 100, with everything spread out wider in between?

Because in America we have a strong tradition of constructing tests so that the average

student, a student who is solidly passing but not exemplary, will get something like 80%

of the questions right. We Americans have been brought up on that tradition and can hardly

make up tests any other way (although I assure you that in other countries it is done!).

By grading on a scale of 50 or 60 to 100, we can still use test scores as grades,

without further conversion. The average students are in the middle of the scale.

(The relevant mathematics here is the concept of

ordinal, interval, and ratio scales.

Grades have to be an interval scale, so they can be averaged; they do not have to be a ratio scale,

because we do not interpret them as showing that one student knows twice as much as another;

actually, a grade of 100 is probably a lot more than twice as much knowledge as a grade of 50,

and always has been.)

Afterthought: The practical question is whether you want to penalize students

heavily for not attempting assignments. If that is the case, then the old system is better

(0 for a missed assignment, 60 for a barely passing one).

But if you think missed assignments are usually comparatively accidental, it is fairer

to give a score just short of passing, to avoid doing so much damage to the

student's grade. That is the rationale for the new system.

Permanent link to this entry

Michael Lee Dowse, 1952-2018

I am sad to bid farewell to a high school companion whom I haven't seen in twenty years, but

whom everyone remembers as mild-mannered, kind, wise, and mature.

Actually I wasn't in high school with "Mouse" (a collapsed way of pronouncing his name; he did not resemble

a rodent in any way I could see!).

We were in The Action Trav'lers,

a remarkable youth travel club in Valdosta about which I shall write more later.

He will be missed.

May his memory be eternal.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

26

|

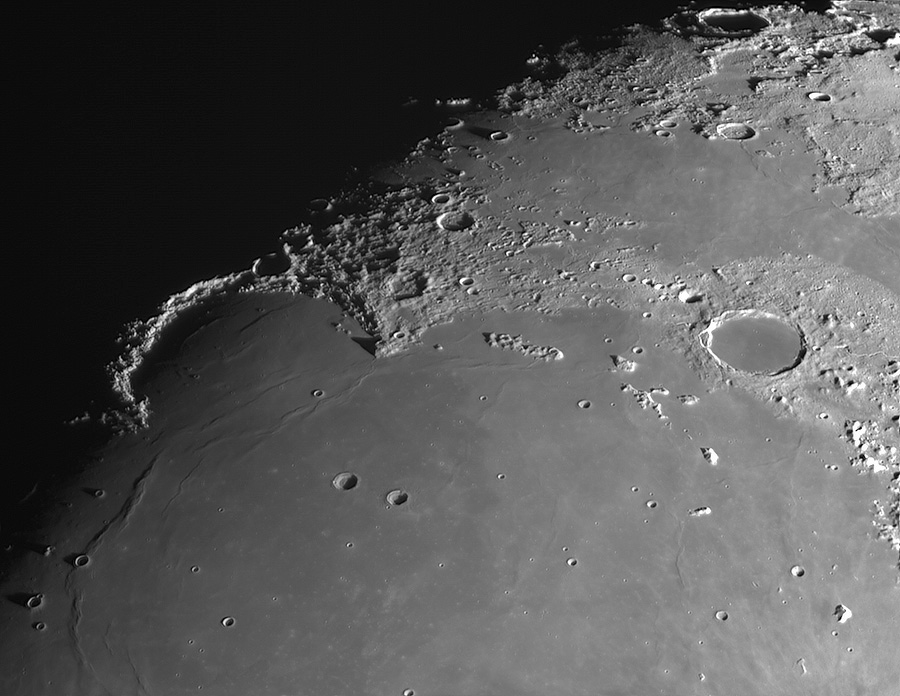

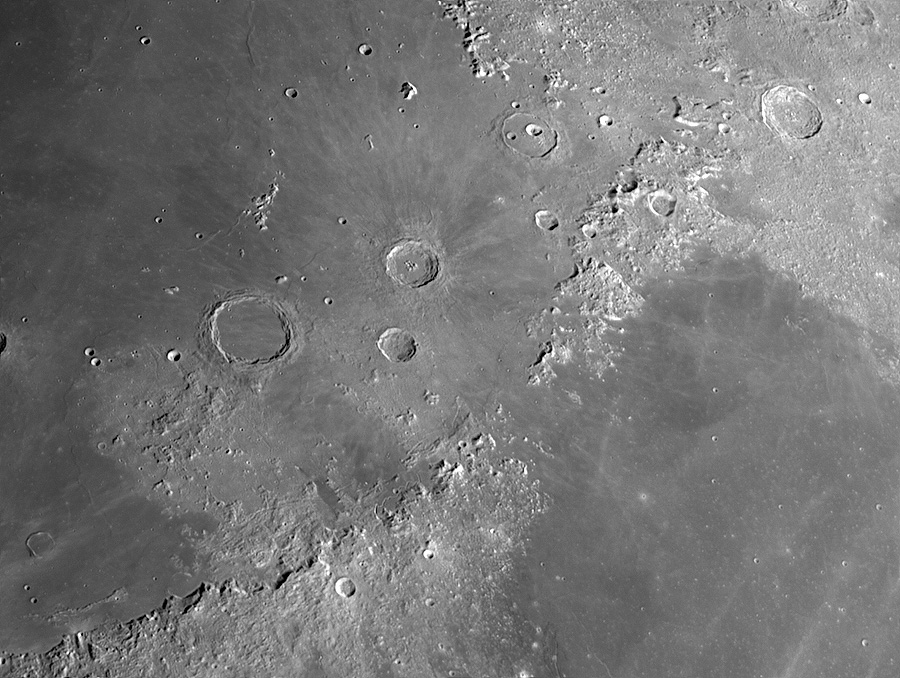

The moon at lower magnification

Here are a couple of wide-field views of the moon, taken with my vintage 1980 Celestron 5

and the ASI120MM-S camera (with an infrared-pass filter; these are infrared images).

A field including Oceanus Procellarum.

The very leftmost thing in this picture is a mountain range surrounding Mare Orientale,

right on the edge of the visible face of the moon:

And here is a partly overlapping view a little farther south,

with Mare Humorum prominent:

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

24

|

Do "all boys do that in high school"? No!

From a Facebook posting that was very well received...

"Don't all boys do that in high school?" said someone about Judge Kavanaugh's alleged behavior with Christine Ford in his student days.

That is a terrible slander against all males, and I won't stand for it.

(Please note that I have no inside information about what Kavanaugh actually did, and do not want to discuss that.

The question here is whether what he is accused of is serious.)

And the answer is, it is serious.

There is a huge difference between making advances that a girl can accept or decline,

and violently holding her down, covering her mouth, and making her think she's about to be raped.

Someone has failed to make a crucial distinction.

Portraying all healthy males as rapists is a terrible slander.

It would imply that we are all a violent menace and can't be left alone with anyone else. It's not true.

[Follow-up after getting about 30 "likes":]

I am glad to see so many people confirming what I said.

I was wondering if I had led an unusually sheltered life — and so had hundreds of my friends!

I know that the behavior described does occur, and has been regrettably common

(especially in the confusion of the 1970s), but it's not "normal" or excusable.

Women who believe that all men are rapists —

unless they're just gullible — must have seen terrible examples of maleness.

[Follow-up:]

Spreading the false message that most or all men are dangerous is a setback not only

for men's rights, but also for women's rights.

If a prudish society decides that women must be "protected" by not being allowed in the

presence of males, most work opportunities for women will disappear.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

23

|

Danielle Leigh Glisson, 1988-2018

Going to the funeral of someone a generation younger than me would have been

a disconcerting experience even if the deceased person were not my niece.

But in fact it was Danielle Glisson, Melody's sister's daughter, born the

same month as my daughter Sharon; she passed away after a harrowing two-month

bout with meningitis. To see a PDF copy of the obituary,

click here.

Lux aeterna luceat ei, Domine, cum sanctis tuis in aeternum.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

22

|

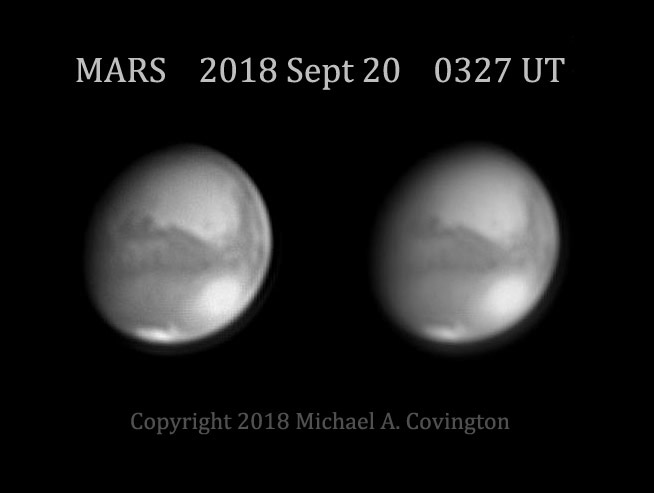

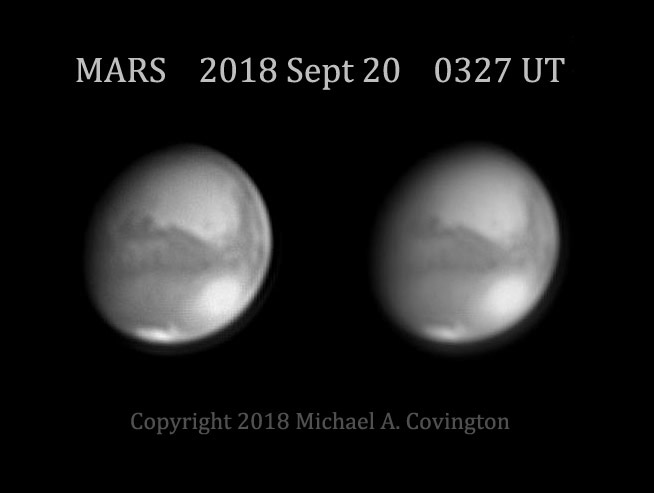

The "rind" on the edge of images of Mars

On the evening of the 19th, we had exceptionally steady air, and even though Mars and the moon

were only about 30 degrees above the horizon, I got sharp images of them. Above you see Mars,

a stack of the best 50% of about 7000 video images taken with a Celestron 8 EdgeHD, 3× extender,

infrared-pass filter, and ASI120MM-S camera. This is an infrared image.

The image has been processed two ways. The first image shows lots of detail, but also an

artifact called the "rind" on the right-hand, sunlit edge of Mars.

The image on the right has been processed with a deringing filter to suppress the rind,

but it has lost some detail.

The "rind" only shows up on very sharp edges, notably the sunlit edge of Mars, though I've also

been troubled with it in images of Saturn and Jupiter. Notice that it is not present on the

softer edge of Mars (actually the terminator region), away from the sun.

For years we have all assumed that the "rind" is caused by "ringing" (overshoot) in the

digital sharpening algorithm — but deringing filters don't get rid of it unless they

are so strong as to harm the central part of the image too.

Now some very interesting

research by Martin Lewis

has convinced me the "rind" is actually diffraction in the telescope,

analogous to the rings we see around a highly magnified star.

That is, the "rind" is really present in the image that the telescope forms,

though it takes a lot of digital sharpening to bring it out.

Like diffraction and unlike anything else, the size of the "rind" is proportional

to wavelength. I'm using infrared, so on my images, it's as big as it can be.

Along the way Mr. Lewis investigates several other causes of ghost edges and bright edges,

including real "ringing" (which does happen) and several kinds of electronic or digital

echoes within circuits.

This is an issue worth pursuing!

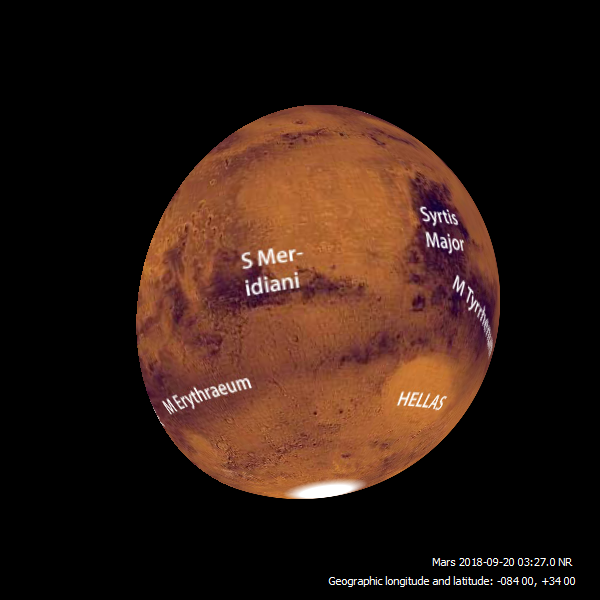

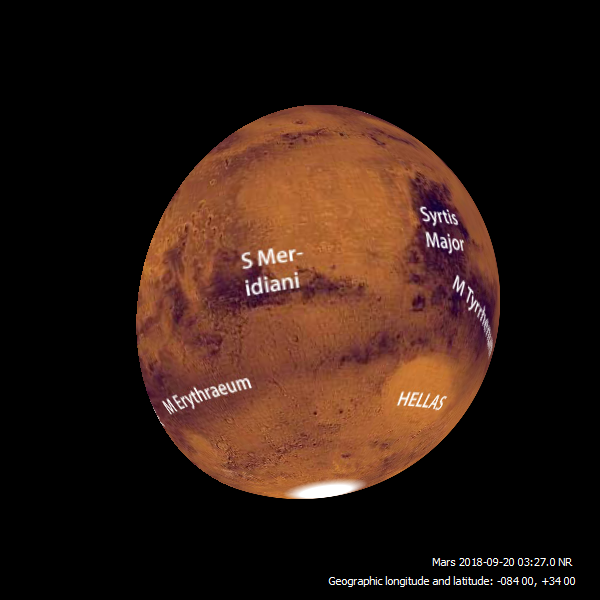

For the curious, that view of Mars corresponds to this map:

Permanent link to this entry

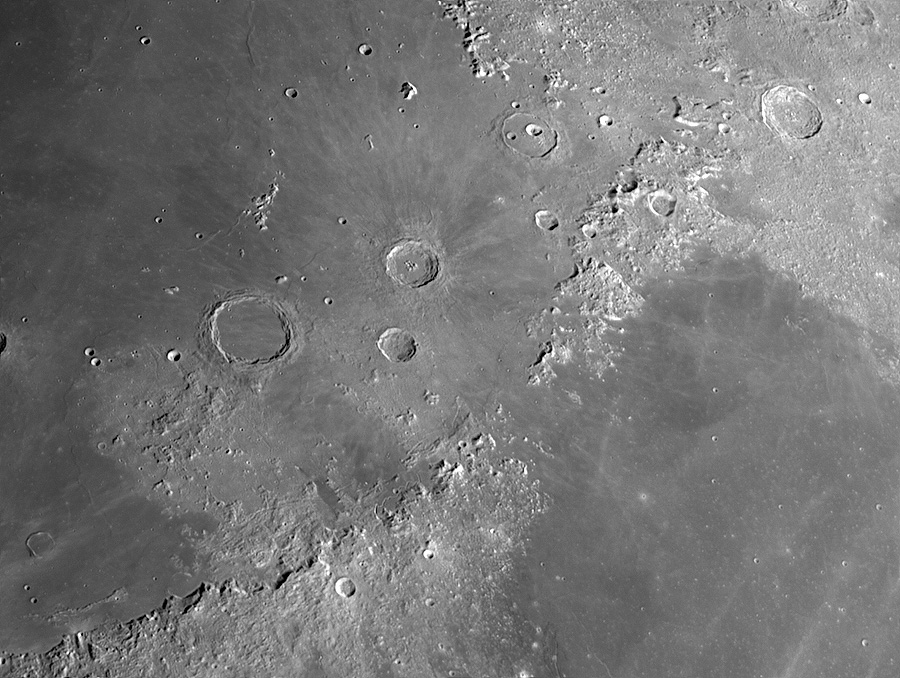

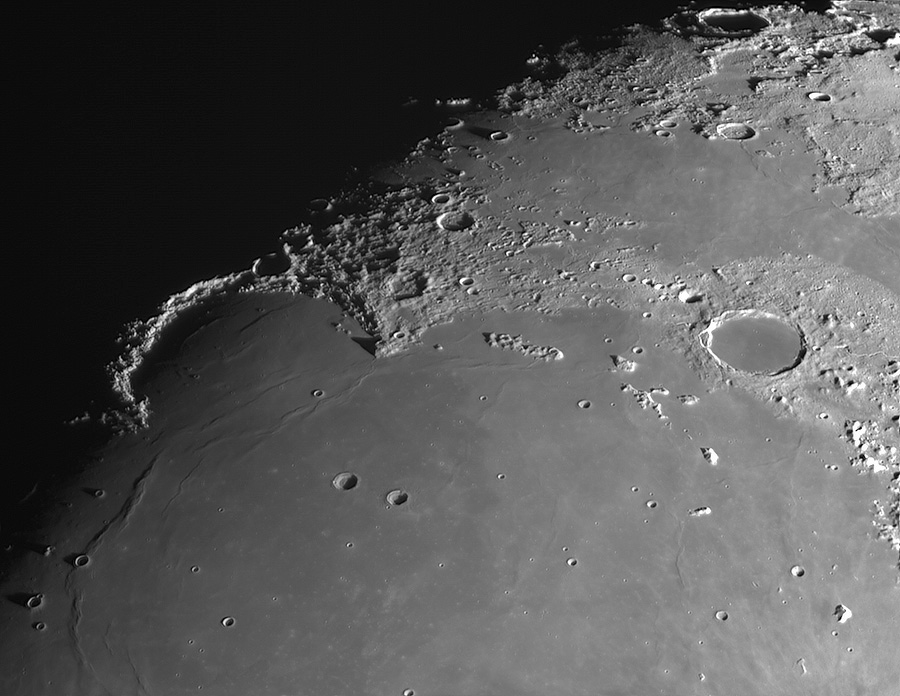

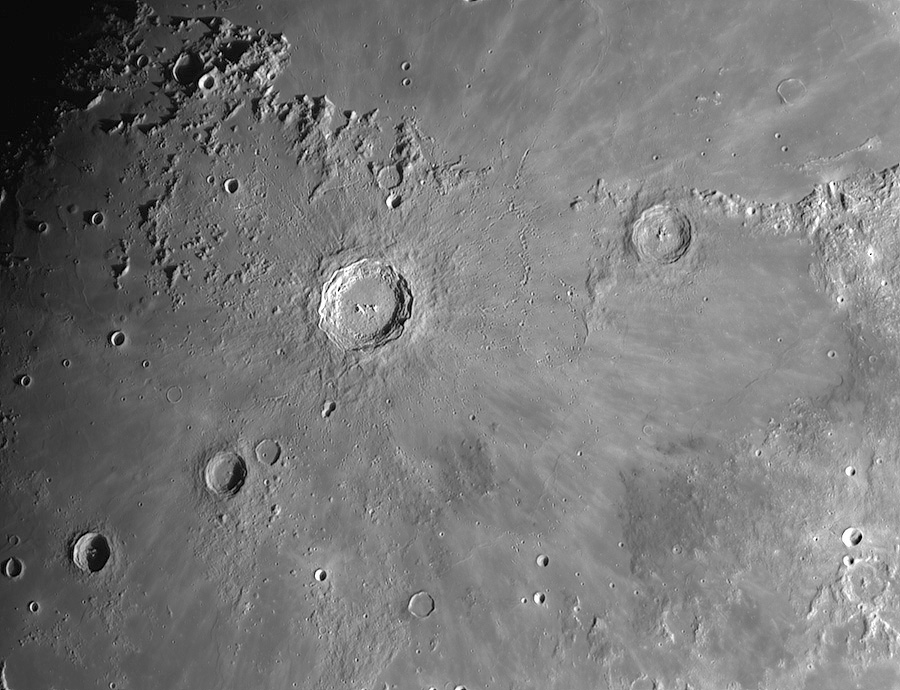

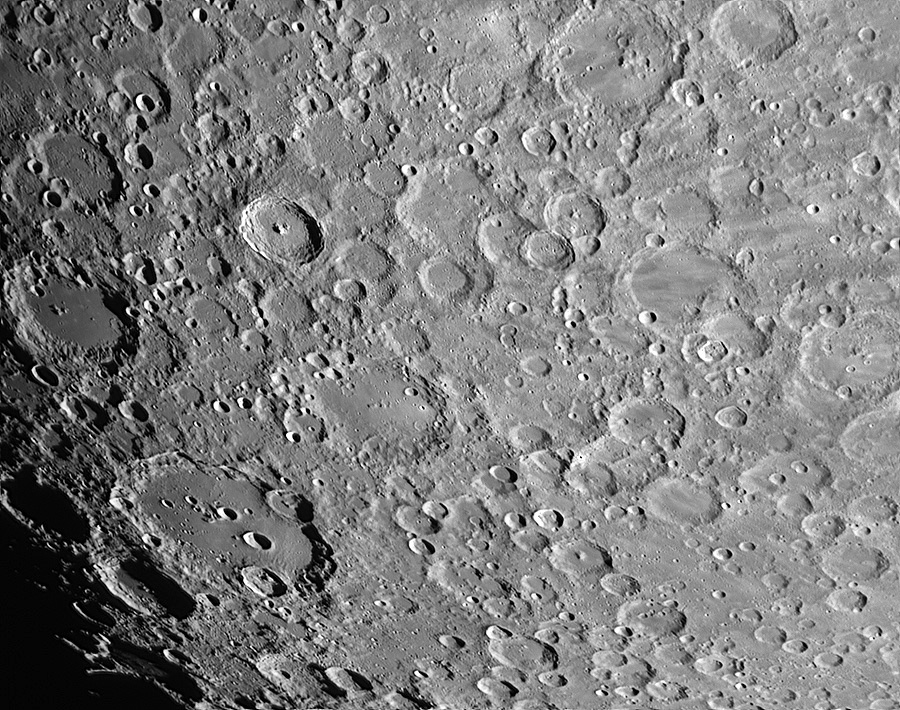

A walk across the moon

I am delighted that, with the C8 EdgeHD at f/10, IR-pass filter, and ASI120MM-S camera, I can

get sharp, large, wide-field views of the moon.

Here are several scenes, walking across the face of the gibbous moon from

north to south.

Each is a stack of the best 50% of about 3600 video images,

processed with digital sharpening and HDR adjustment.

Enjoy the subtle detail — not just the craters and mountains,

but also the shadings and ripples.

Plato and Sinus Iridum:

Copyright 2018 Michael A. Covington. Copyright information is embedded in the image file.

Archimedes:

Copyright 2018 Michael A. Covington. Copyright information is embedded in the image file.

Alphonsus (with central peak):

Copyright 2018 Michael A. Covington. Copyright information is embedded in the image file.

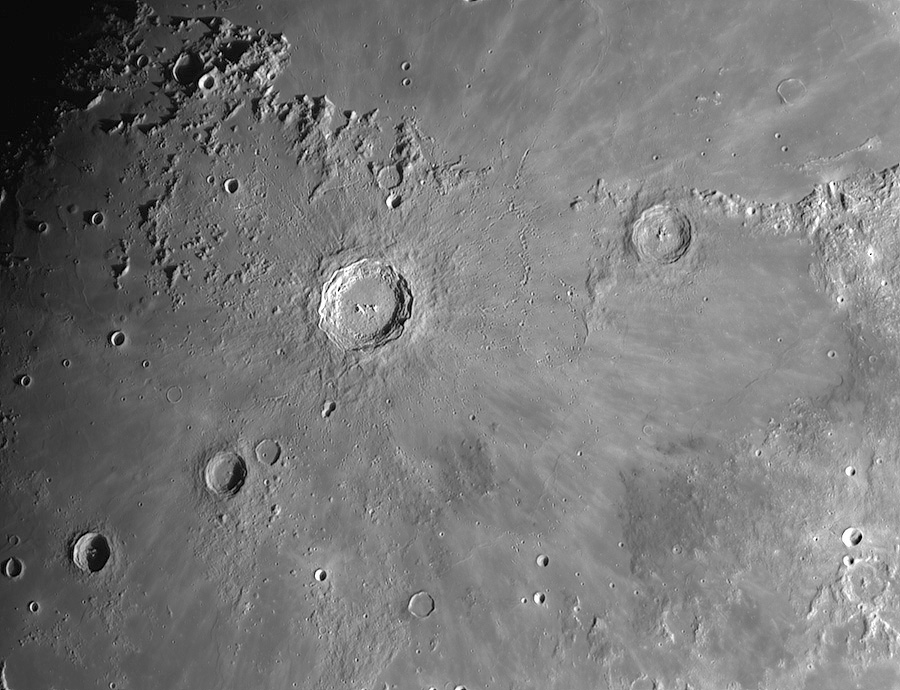

Copernicus:

Copyright 2018 Michael A. Covington. Copyright information is embedded in the image file.

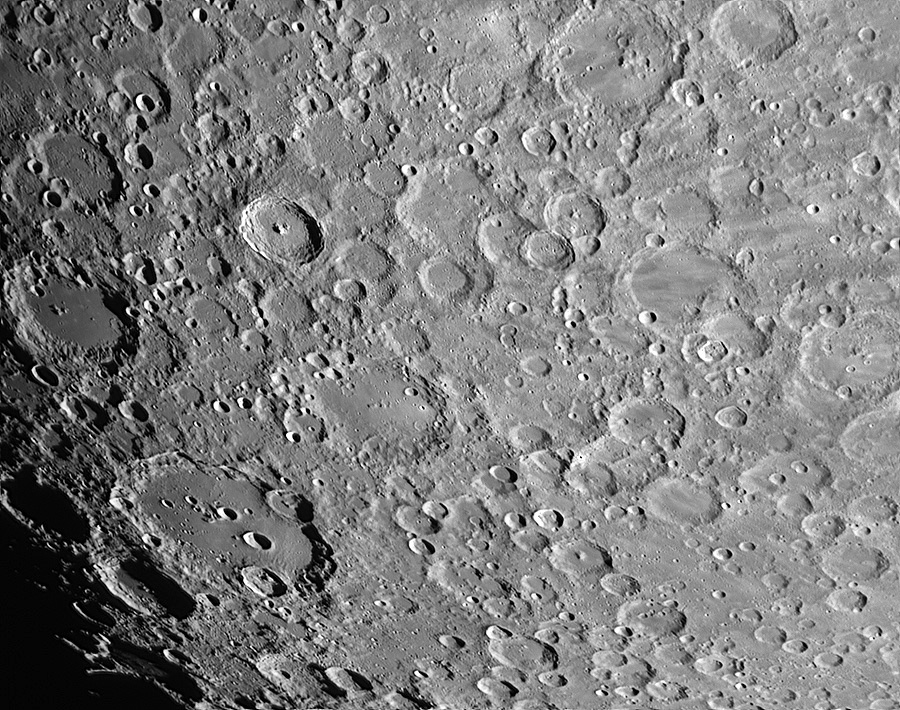

The heavily cratered south, with Tycho and Clavius:

Copyright 2018 Michael A. Covington. Copyright information is embedded in the image file.

Clavius is at the lower left corner, a large crater with an elegant curved row of

smaller craters inside it. Tycho is higher up, and the impact that caused it left

streaks of material radiating out from it.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

17

|

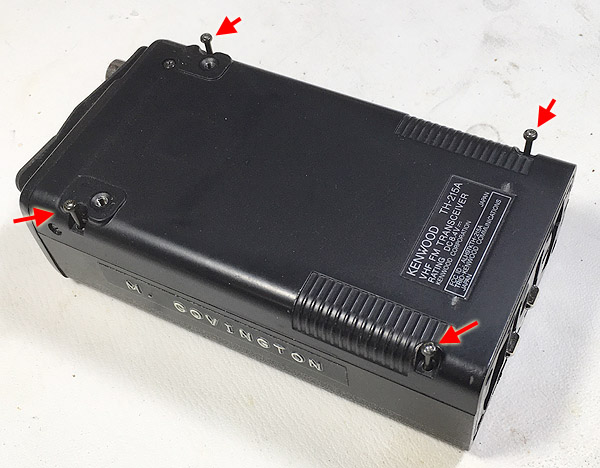

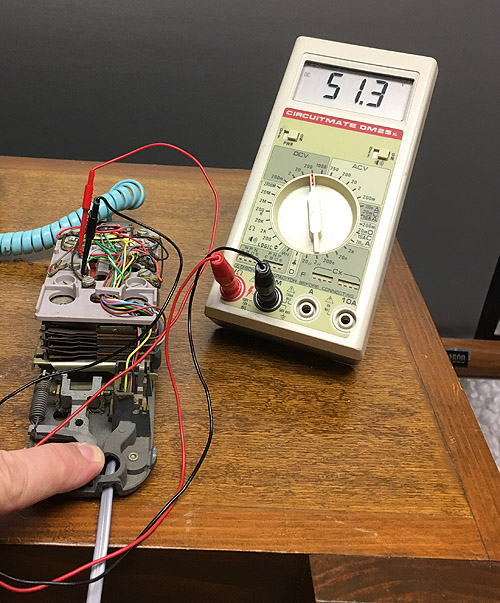

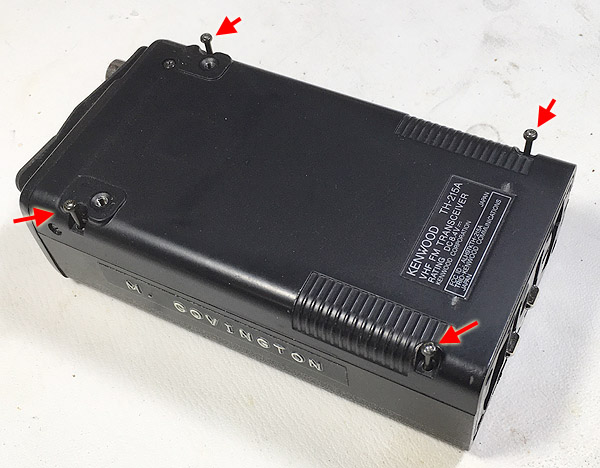

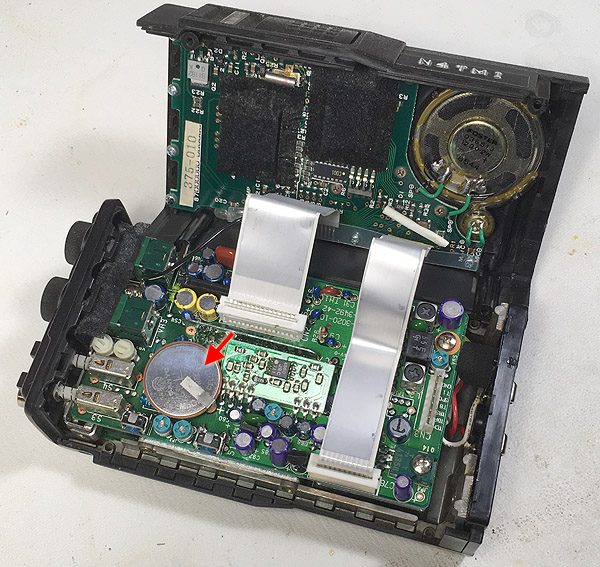

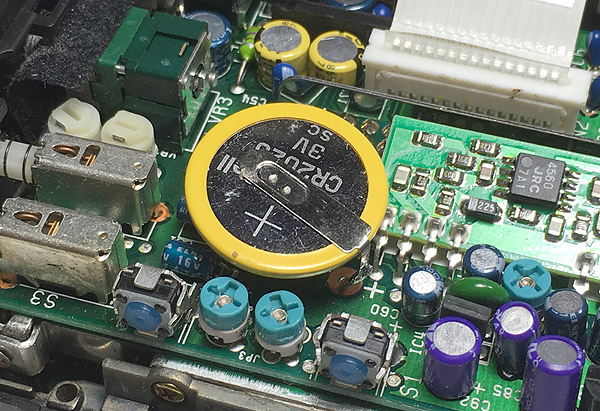

Kenwood TH-215A coin cell replacement

The Kenwood TH-215A ham radio handheld transceiver (HT) uses a lithium coin cell for

memory backup. I bought my TH-215A in 1988, made my very first contact with it when I got

my license, and want to keep it functioning.

Recently, it started losing the channel memories when turned off.

Of course, it needed the coin cell replaced.

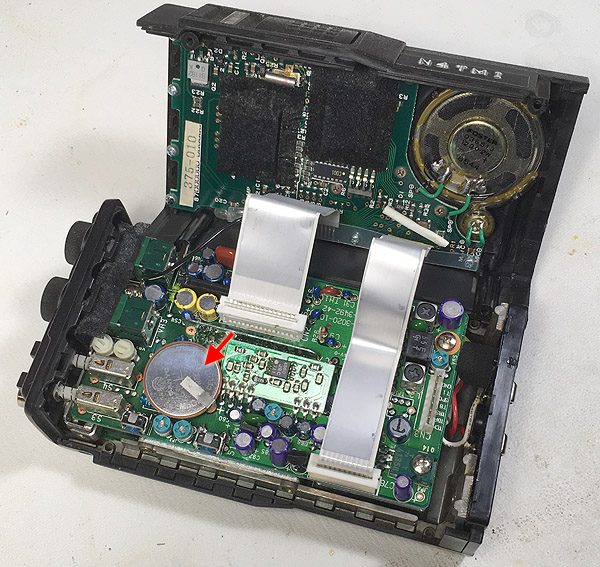

The procedure I will describe here involved tack-soldering a new cell from the top of

the circuit board, without taking the circuit board out. Don't be afraid of tack-soldering;

with enough solder, well melted, it is as reliable as soldering wires that are already

mechanically connected. Tack-soldering means coating both surfaces with a generous glob of

solder (think "glob," not "coating"), then holding them together and re-melting the solder.

Then you have to hold everything very steady while the solder hardens — only a couple of

seconds if you have good 63-37 tin-lead solder.

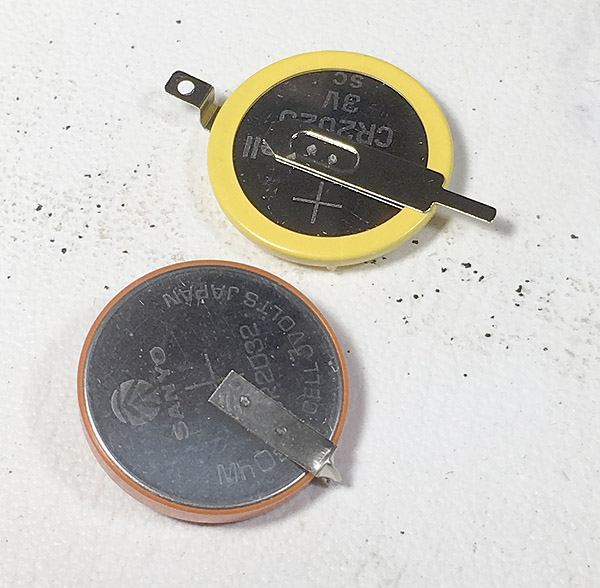

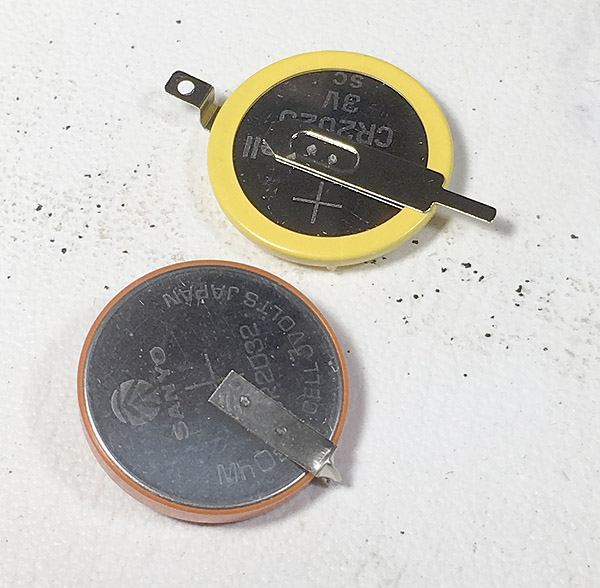

The replacement cell should be equivalent to a CR2032. You can get CR2032s with solder tabs

at Batteries Plus (they put the tabs on while you watch), but I chose to use

this low-priced imported CR2025,

which is slightly smaller (making the repair easier) but may not last as long.

It's a popular item for repairing Pokémon games of some sort, and you may even be able to

get it from a computer game dealer.

(My original coin cell failed 30 years after I bought the transmitter; it was a couple of years

old already then. Maybe the new one will only last 20 years. That's good enough!)

The photography here was done hastily with an iPhone and is not up to my usual standard.

If I were writing this up for a magazine, the pictures would be much better. As it is, I'm

writing a Daily Notebook entry in haste.

Step 1: Remove the antenna and battery pack. Then remove the belt clip, if present (2 screws, Phillips #2).

Step 2: Remove the 4 corner screws (Phillips #1 or #0).

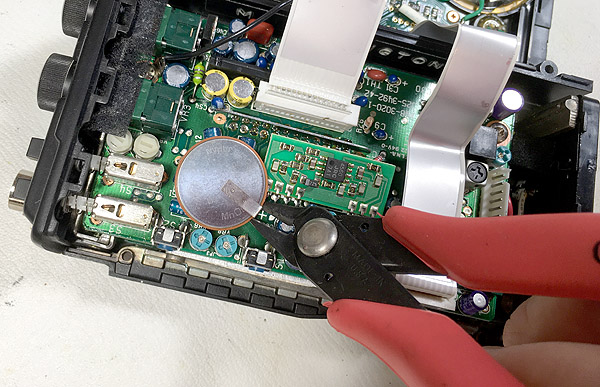

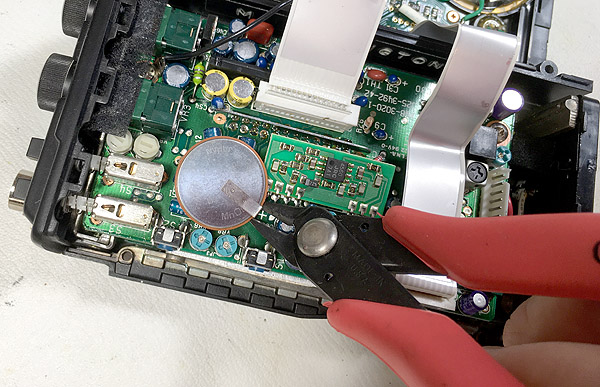

Step 3: Flip the radio over (keypad up) and open it from the front. The cell you are replacing is marked with the red arrow.

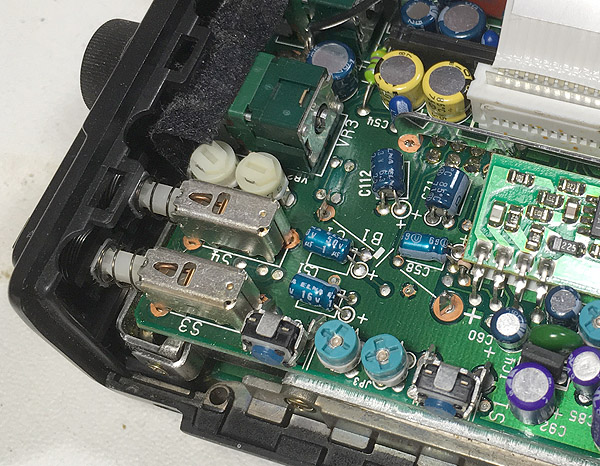

Step 4: Clip the tabs of the existing cell, one at a time, taking care not to short them together.

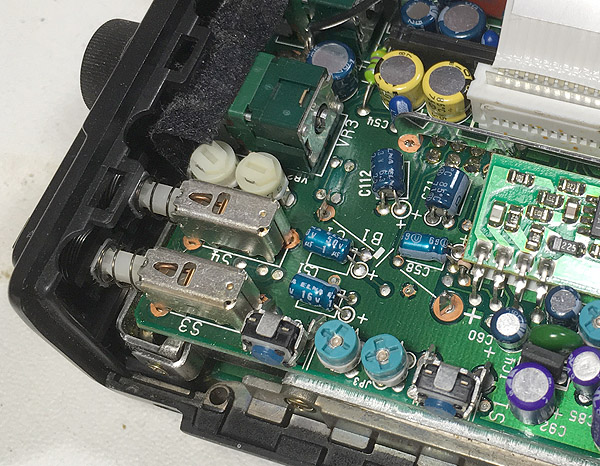

Step 5: You will have two tabs left on top of the circuit board. Straighten them if they are bent and tin each of them

with a generous glob of solder (maybe 0.5 mm thick).

Step 6: Test the replacement battery to verify voltage (about 3.3 fresh) and polarity.

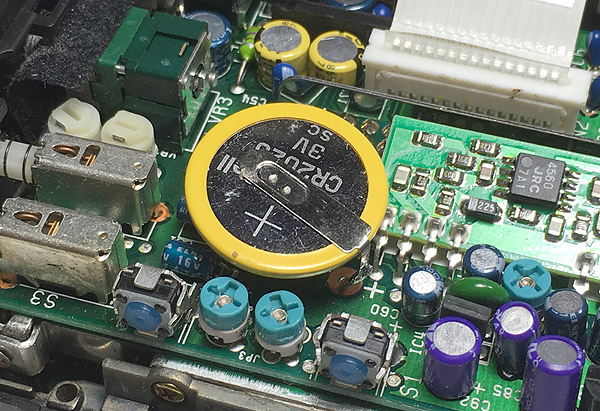

Step 7: Bend the tabs of the new battery as necessary so they will mate with the tabs left

behind on the circuit board, and tin them generously with globs of solder.

Then tack-solder the new battery in place, first the negative tab, then the positive one.

Step 8: Verify that the new battery is well supported, and reassemble the radio.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

16

|

Ageōmetrētos mēdeis or oudeis eisitō?

Today I venture again into my original field, historical linguistics, and present

what I think is an unsolved problem of Classical Greek philology

(and a question people often ask on Google).

If I find out the answer, I'll post it here.

The motto of Plato's Academy is normally quoted as

ἀγεωμέτρητος μηδεὶς εἰσίτω

ageōmetrētos mēdeis eisitō

Let no one ignorant of geometry enter

with some variation of word order. It is actually attested only from the Middle Ages.

A better translation might be, "No one without geometry shall enter," since the verb is

a third-person imperative; the English word "let" in the translation doesn't mean "allow."

Historians argue whether it meant you had to master geometry before entering or just

display a talent for it.

However, in a few famous places,

including

the title page of Copernicus' De Revolutionibus,

the motto is quoted with οὐδεὶς (oudeis) instead of μηδεὶς (mēdeis).

(If you click through to Copernicus, note also the ligatures for tr and ou,

typical of Byzantine manuscripts and early printed books; we print our Greek more simply now.)

Oudeis and mēdeis both mean "no one."

The difference is that ou is used with indicative verbs and mē with non-indicative verbs.

Since the verb here is imperative, mē seems to be what the grammar calls for.

So the question is, how did the version of the motto with ou get into circulation,

and is it within the bounds of Greek grammar?

It may be grammatical, just barely, a deliberate attempt to shift the meaning toward declarative

("nobody without geometry gets in").

Or someone unfamiliar with third-person imperatives may have simply made a mistake.

At present, though, I can only describe this as an unsolved puzzle.

Useful references:

Wikipedia;

a 6th-century source

(Elias' commentary on the Isagogē and Categories; look at p. 118 lines 13-19);

article by H.-D.

Saffrey in Revue des Études Grecques 1968.

[Update:] My best theory, after having checked with Greek scholars, is that oudeis is a mistake

that arose in Renaissance times and then got quoted afterward. I have not found an instance of it

earlier than Copernicus (1543), but I've found it quoted in 19th-century books that are not astronomy-oriented

and thus probably didn't get it from there. The mistake may even have arisen more than once.

If you remember most of the motto, but are unsure whether it has oudeis or mēdeis,

you're likely to pick the wrong one unless you remember the grammar of third-person imperatives,

which is a rather advanced part of Greek grammar. People with a first-year student's knowledge of Greek

can get

it wrong — may even be more likely to get it wrong than to get it right.

Permanent link to this entry

-able or -ible?

Melody asked me whether collectable or collectible was the correct spelling.

She was daunted by the elaborateness of the answer I gave, but that's nothing compared to

what I'm about to give you. Hang on to your hat...

My first response was, "I'm sure both spellings are in use," followed by, "This is a job for

corpus linguistics." Using Google Ngram Viewer, I quickly ascertained that

collectible predominates in the U.S.

and

collectable in Britain.

I suspect there is also some variation with context (collectable coins vs. collectible debts),

but I didn't pursue that.

Her next question: "Is there a rule to tell me whether to use -able or -ible?"

No, but there are some useful generalizations.

The problem is that the situation has been messy since Roman times; many words are spelled

both ways, and some have settled into a preferred spelling that isn't the one you'd expect.

Latin had both -able and -ible (then spelled -abilis and -ibilis).

They were the same suffix, actually -bilis, and the vowel in front of it came from the

verb to which it was attached.

So a-stem verbs had -abilis and e- and i-stem verbs had -ibilis.

From this, in English, we have portable, inflatable, visible, incorrigible.

English also borrowed -able as a productive suffix (matching our word able) and

attached it to verbs that were not Latin, such as lovable, trackable, and so forth.

But English also borrowed -ible and started putting it onto words that sounded as if

they ought to have it — generally words with e's and i's in them, especially if they are

derived from Latin.

And there it gets even more messy. When a Latin verb is borrowed into English and changes its form, can

we still put -able or -ible on it? If the root of collect had taken a

suffix in Latin before coming into English,

it would have been colligible (compare corrigible).

But it didn't. Collect came over into English and then we put a suffix on it.

And that's where people couldn't make up their minds.

Another source of messiness is the tendency of Late Latin to make a-stem verbs out

of other verbs. That gives us -able in a few cases where we wouldn't otherwise expect it;

it may be what is behind transferable.

So are there any useful generalizations? Yes.

- If there is a form with -ate or -ation, then use -able.

Thus transportable (transportation), orientable (orientation).

- If there is a form with -ion (but not -ation), then use -ible.

Thus transmissible (transmission). (This is not exceptionless.)

- -ize always takes -able (this goes back to Late Latin).

Thus recognizable, optimizable.

- If the beginning of the word is not an English verb, and contains no a's,

use -ible; thus visible, corrigible, risible.

(Vis and corrig and ris are not words in English.)

- When in doubt, if you're attaching to a real English word

(whether or not originally Latin), use -able.

It is the more productive of the two suffixes and is almost always acceptable,

even if -ible is also used.

Now you know what Melody goes through, being married to a linguist!

And for the rest of you, why didn't I just look in the dictionary?

Because the people who write dictionaries have to get their information from

somewhere, and I know where they get it.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

12

|

End of Plain Old Telephone Service (POTS)

I placed the order today for our AT&T land line telephone service to end, to be replaced

by a VoIP line coming off our Spectrum Internet connection.

The reasons are twofold.

First, we're paying for VoIP already; it's bundled in our Internet service.

Second, more importantly,

Spectrum offers robocall filtering and AT&T POTS doesn't.

(AT&T does offer it through their "U-Verse" VoIP telephone lines.)

I have pointed out that

robocalls have killed the telephone as we knew it,

and yesterday we got 15 of them, most of them from just two

political surveyors that kept calling over and over.

One of the best solutions is crowdsourced spam-filtering — that is,

detect when an unidentified person is calling a lot of telephones

in rapid succession, and

block them — and that's what

Nomorobo is doing.

They are accessible via VoIP but not POTS.

What are POTS and VoIP?

Well, VoIP is Voice over Internet Protocol, telephone calling by transmitting data packets

through the Internet.

A VoIP modem connects to the Internet and provides a connection for (reasonably) conventional

telephone equipment.

POTS is Plain Old Telephone Service, or "copper," the kind of service that actually requires a wire

all the way from the telephone company downtown to your house.

Any telephone made since about 1900 can receive POTS calls, although it can only originate calls if it

has a dial.

(In some places nowadays, that's not enough, and it has to have a tone dialing keypad.)

The power source is traditionally a 48-volt battery at the central office, actually delivering

up to 52 volts because 12-volt batteries are actually 13 volts, or a little more, when

fully charged.

When the changeover happens, the AT&T line will go dead, and I will go under my house,

disconnect my house telephone wiring from AT&T's incoming wires, and connect it to my

Spectrum VoIP modem. It's that simple. I've already done it as an experiment.

(The VoIP modem already works with a different phone number, which we will give up.)

Thanks to the finicky requirements of ADSL Internet connections (over AT&T's copper)

in past years, high-quality house wiring is already in place, with a star architecture

from a central feedpoint.

Why don't I simply give up my land line?

Because I have telephones installed all over the house and want them to continue to work.

I don't sleep with a cell phone.

And more importantly, in case of a fire or medical emergency, I want to be able to reach

for a phone on the wall, rather than hunt for a cell phone that will probably be in another room

and might not even be accessible.

Permanent link to this entry

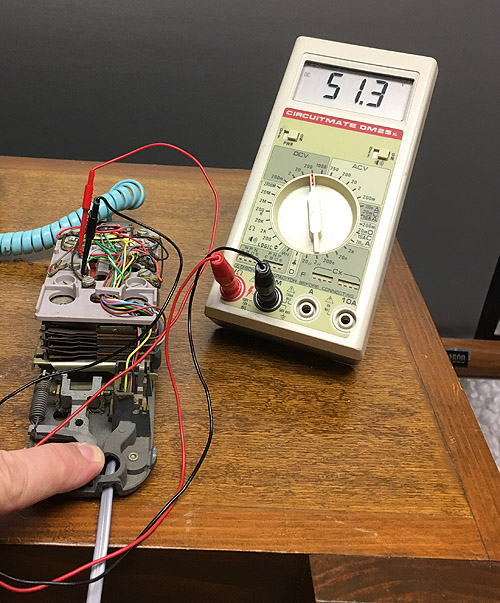

A last attempt at dialing

I haven't dialed a phone call, with a dial, in perhaps twenty or thirty years.

When we switch to VoIP, it will be impossible — I don't think the VoIP modem supports

"pulse dialing" with dials — so I wanted to try it one last time.

Many of my readers have never dialed a telephone at all.

What you do is put your finger in the appropriate numbered hole and use it to turn

the dial clockwise, against spring resistance, until it hits the stop; then you take your

finger out and let go, and the dial turns back, at a governed speed, sending out electrical

pulses as it goes.

Looking at this dial, you might think dialing 1 would be a no-op (no movement at all).

In fact, though, as soon as you start dialing, the stop moves to some distance past

where the 0 is.

More traditional dials

have a gap between the 1 and the 0, with the stop in a fixed position.

Well, I dug out this circa-1980 Trimline phone

(probably made around 1965 and updated later)

and connected it to the line.

I found I could dial and listen but could not talk — its transmitter (microphone)

no longer works. But at least I took a few pictures, including one showing the battery

voltage across the line.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

11

|

What do we mean by "define 'planet'"?

The debate about Pluto has made many people think deeply for the first time about

the nature of definitions and classifications. In particular:

Do we classify things by what they are or where they are?

If you are studying pickup trucks, the distinction between "truck in the country" and

"truck in the city" is easy to make, but it doesn't give you much help understanding

how they work. On the other hand, the distinction between "truck with a diesel engine"

and "truck with a gasoline engine" is quite revealing — helps you understand more

about how the truck does what it does — even though you have to examine the truck

more closely in order to make it.

Must classifications be sharp?

If you are a librarian, you have to classify books sharply.

It may be unclear whether a book is about astronomy or physics, but you have to label it

one or the other in order to put in on the shelf.

But nature does not work that way. Some classifications in nature are sharp, especially

biological classifications; every creature has definite ancestry, imposing a classification on it.

But other classifications are not. Is Australia a smallish continent or a giant island?

Is 99.2 F a fever? In science, when we encounter a continuum or a fuzzy boundary,

we should admit it, rather than making up a sharp criterion that doesn't have physical

reality.

Traditional classifications are often based on small samples.

Often, we discover a few examples of something; they seem to fall into neat categories;

and then we discover more, and the neatness breaks down.

That is what is happening with planets right now.

Words can change meaning while still referring to (mostly) the same objects.

This happens routinely as we learn more about the world.

To us, water denotes dihydrogen monoxide; to the ancients, a handy

substance found in rivers, wells, and rain. They are the same thing, but the criteria

in people's minds are different — and the criteria are not tested in everyday life

because we never encounter anything that they classify differently (well, probably).

Here is a medical example. Diabetes used to mean "excessive urination." As the causes

of excessive urination were discovered, doctors distinguished diabetes mellitus (a common defect

of sugar metabolism) from diabetes insipidus (a quite unrelated pituitary gland disorder).

You can have either one without excessive urination.

The old meaning of the word was simply left behind.

Now then. As we have discovered more about planets, we have changed the meaning of "planet"

from "movable bright dot in the sky" to "object that orbits the sun" and then to

"relatively large object that orbits the sun" (they kicked out the asteroids in the mid-1800s,

in a crisis similar to what we're now having about Pluto). And now we've discovered so many

Kuiper belt objects, some of them apparently bigger than Pluto, that the situation has become

very messy.

One possibility would be to throw out the word "planet" altogether, except as a historical term.

Use it casually to denote the same things it has always denoted, and not use it as a precise

scientific term at all.

Another is to try to devise a scientifically useful definition of "planet" that still picks out

the traditional set of objects (with minor adjustments). Both the IAU and I have tried to do this.

They kicked Pluto out; I want to let Pluto back in, and admit that this means Ceres, Eris, and quite

a few other objects are also planets.

Where I part ways with the IAU is that I want to classify planets by essential, not accidental,

properties. That is a technical way of saying that I want to classify them by what makes them

what they are — not by their circumstances. The presence or absence of other objects in the orbit

doesn't affect what the planet is, so let's not use it.

(I do keep the distinction between planet and satellite, purely for convenience, even though it is an

accidental property; Mercury and our moon are very much the same kind of object, but they orbit different

things.)

Now then. Where did I get all these tools of thought? From Aristotle, Aquinas, Ockham, and

other ancient and medieval philosophers. They laid important groundwork for modern science, yet today

they are ignored, and many imagine they were stupid and mired in superstition. (Well, at least Ockham

gets a little respect occasionally.) I learned about medieval philosophy while

researching this

in the early 1980s. (Published 1984, despite what the web page says.)

It comes in very handy in my current work with machine learning and artificial intelligence.

Meanwhile, those who think medieval philosophy is bunk are having to re-invent large parts of it.

And I've had people say, in the discussion of Pluto, "I'm not interested in philosophy of science,"

to which I can only reply, "You're arguing about it right now."

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

10

|

Why we can't still have 9 planets

And a proposal for a better definition of "planet"

People are still arguing about whether Pluto is a planet, and some are

asking why we can't still use the list of 9 planets that we memorized in

elementary school.

The reason is simple, important, and not well enough known:

More planets have been discovered!

Eris and Haumea are very much like Pluto;

Sedna is even farther out; and there are plenty more

where they came from.

More about that here.

Faced with that situation, astronomers could either add all these to the list,

ending up with dozens of planets (many of whose status was uncertain), or else

narrow the definition of "planet" and go back to eight.

The IAU voted to do the latter, but I'm going to argue against their decision.

Think for a moment about the history of the question.

In ancient times, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn were the

planets.

They look like stars in the sky, but their position changes.

Copernicus added Earth to the list; previously people hadn't realized

that the earth orbits the sun.

So things stood until we started getting planets that can only be seen

with a telescope: first Uranus (discovered in 1781), then

Ceres, Pallas, Juno, Vesta (1801-1807), some others,

and eventually Neptune (1846).

This

1850 textbook lists 18 planets.

But was quickly realized that Ceres, Pallas, Juno, and Vesta were part of a swarm

of small objects now known as the asteroid belt.

So after being added to the list of planets, they were taken out.

It was also realized that Uranus and Neptune were nearly as big as Saturn;

their status was secure.

So we had 8 planets until 1930, when Pluto was discovered and triumphantly added

to the list as the 9th. But right from its discovery, people remarked that it was

unusually small (certainly no match to Neptune) and had an unusual orbit.

More recent discoveries have shown that Pluto has the same problem as Ceres: it's part

of a swarm. That's why it was removed from the list of planets.

But read on...

Permanent link to this entry

A better definition of "planet"

I want to propose a better definition of "planet" than

the one adopted by the IAU.

I am concerned with objects that:

- Are big enough to be held in a round shape by their own gravity (not small irregular rocks);

- Are not big enough to start hydrogen fusion (i.e., are not stars or protostars).

Recent research by Chen and Kipping has shown that

such objects fall into three natural classes,

earth-like, Neptune-like, and Jupiter-like, depending on the physical processes

that predominate at different points in the size range.

I acknowledge that objects of this type include not only ordinary planets, but also larger satellites

of planets (our moon, Ganymede, Callisto, Titan, etc.) and larger members of the asteroid belt (Ceres, etc.)

and Kuiper belt (Pluto, Eris, etc.). On the other hand, smaller asteroids and smaller planetary satellites

are outside this class; they are irregular rocks.

Nonetheless, as a convenience, I want to keep the distinction between "planet" and "satellite" for

objects that orbit the sun (or a central star) vs. objects that orbit planets.

I acknowledge that it can break down if a planet and its satellite are about the same mass;

in that case you would have a double planet.

My definition does not care whether an object is part of a swarm.

By my definition, Pluto is a planet, and so is Eris, and so is Ceres.

We have an uncertain number of planets, and a large number of objects that are on the

borderline between being planets and irregular rocks, and in many cases we can't tell.

But that's a truthful description of nature. It's what's out there!

From the human perspective, it's important to acknowledge that some of these planets are more

prominent than others:

- Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn are visible to the unaided eye.

- Uranus and Neptune require a telescope, but are big.

- Pluto was discovered long before the rest of the Kuiper Belt.

On the other hand, Ceres, Vesta, Juno, etc., have been known to be picayune almost from the moment

they were discovered.

So, from a human perspective, it still makes sense to pay more attention to the historic planets than

to the newly discovered ones.

One last note.

The IAU's criterion was actually even stricter than "not part of a swarm." It said the planet had to

have "cleared its orbit" of other matter, but as Philip Metzger

points out, no planet does that completely, and nobody seems to use the criterion for any other purpose —

it seems to have been made up in order to demote Pluto.

See also above, for more discussion.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

7

|

Bizarre politics

In response to Woodward's book (only partly released so far) and the anonymous

op-ed piece in the New York Times, I have only two comments.

(1) What matters here is truth. There's been too much talk already about how

people feel, or what they wish, or who would benefit. The key question, though, is

whether the claims of these writers are true. I know Woodward and the Times

both have good reputations, but I eagerly await confirmation or disconfirmation by

separate evidence. If the reports are true, the facts have to be faced, whether or not

people like them.

(2) If Trump's staff believe that they cannot in good conscience allow him to

exercise the office of President, they should call for a lawful process to remove him,

either impeachment or the 25th Amendment. What they are reportedly doing now merely puts

them on the wrong side of the law without solving the problem.

Admittedly, such moves as hiding papers so he won't sign them

may be the well-intentioned efforts of people who are at their wits' end, but it's not

sustainable. Let's follow the law of the land.

Two updates:

(a) I said these things on Facebook before Senator Warren said the same thing.

The same thoughts must have occurred to many people.

(b) How would you feel if a popular president were being interfered with by

an unpopular faction among his staff, rather than the other way around?

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

4

|

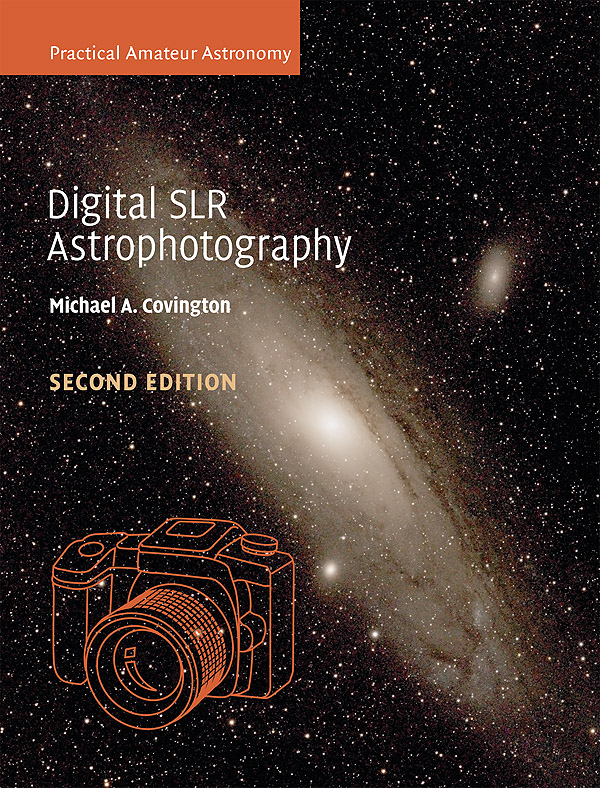

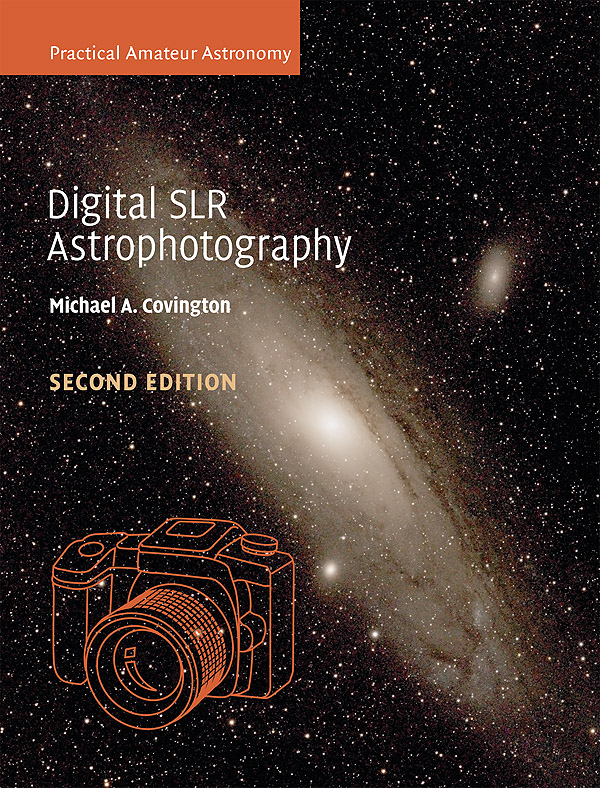

It's a book!

Release of my latest book is imminent — it will become available in Britain later this month and in the USA by

November. Advance orders are being taken, and the book has

a freshly revised web page.

You can view

the table of contents

and

sample pages.

The publisher allowed me to keep making revisions until the last minute, so that, for example, the 64-bit version

of DeepSkyStacker is in it.

And even though the book isn't out yet, it already has a page of

updates and notes.

Permanent link to this entry

|

2018

September

1

|

Politics is not a sport like football or basketball

If you understand nothing else about politics, please try to understand this:

Politics is not a game with a "winner" and a "loser" like football or

basketball. Elections have winners, but winning is not, or should not be, the

same thing as in sports.

The winner of a football game celebrates, and the loser mourns. The loser gets

basically nothing. But the goal of politics is not to impose defeat on a loser.

It is to govern the whole country well, not just the people who voted for

the winning candidate or party.

My good friend Douglas Downing expressed this point eloquently

in his blog:

"When

one group successfully implements its

policy in a way that hurts and humiliates

others, we shouldn’t think of that as a win

for one side and a loss for the other side.

We should think of it as a failure of the

system and look for ways to get a better result."

When Googling to find this, I found that many others

have expressed similar thoughts.

The goal of politics is good government, not defeat of some people by others.

Permanent link to this entry

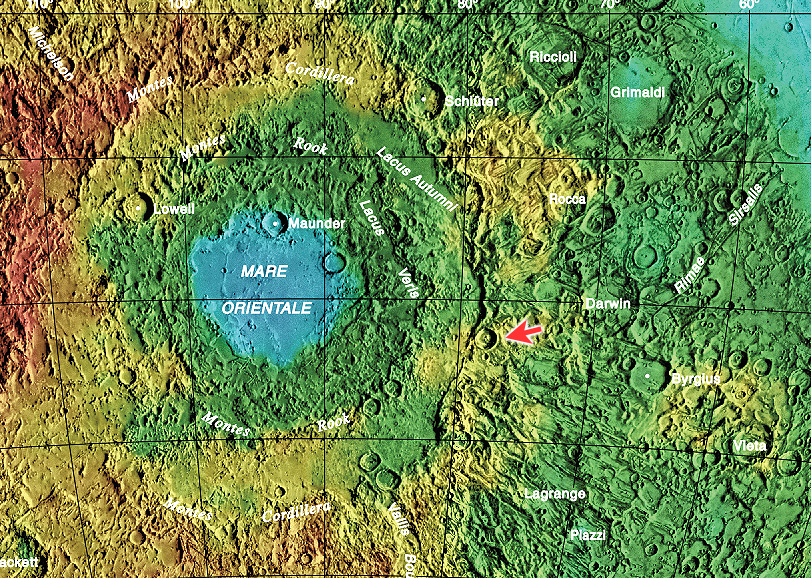

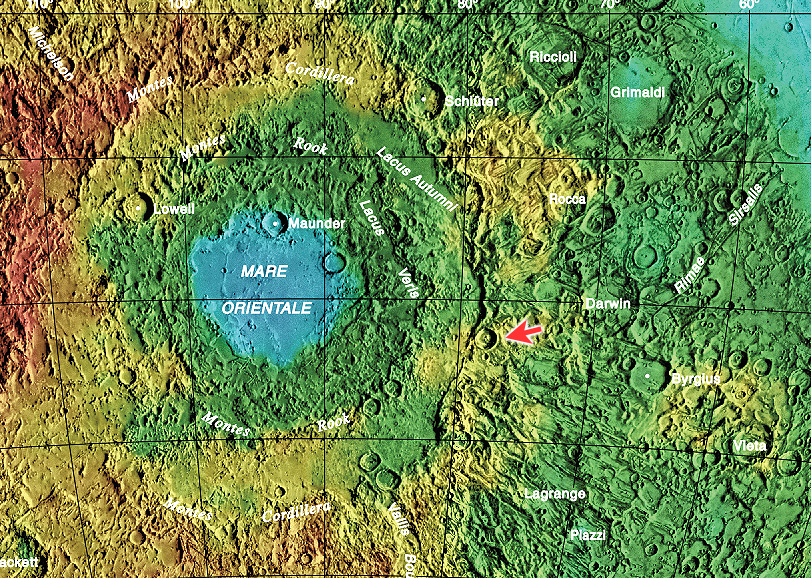

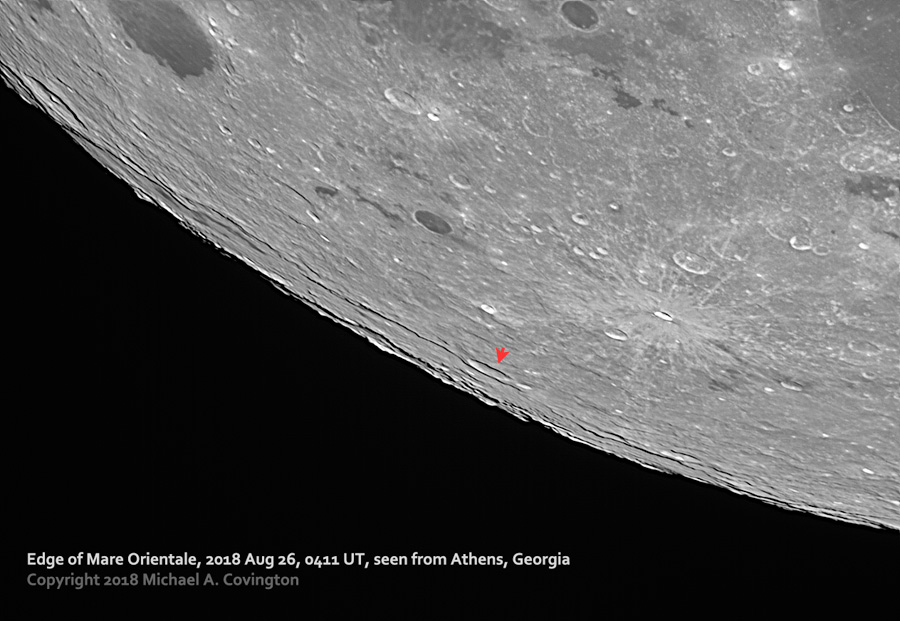

Ramparts of Mare Orientale

Mare Orientale is a huge round plain on the moon,

surrounded by concentric mountain ranges.

Almost all of it is on the "back" side of the moon, which

never faces earth, so its amazing structure was not appreciated

until space probes photographed it. Here is a

USGS topographic map based

on space probe images (ignore the red arrow for right now):

But can you see any of this from earth?

In fact, yes, and indeed Mare Orientale was discovered from earth,

though not fully appreciated.

To see Mare Orientale, we have to wait for favorable lunar libration.

The moon keeps the same face to the earth at all times, but not perfectly; it seems

to wobble a bit because its orbit is not a perfect circle and we're not viewing it

from the center of the orbit. This gradual wobble, over a period of days, is

called libration.

When the moon is almost full and lunar libration shifts Mare Crisium slightly away

from us, that's when we observe Mare Orientale, or at least the mountain ranges

that surround it. Here's my latest attempt.

(8-inch telescope, ASI120MM-S camera, IR-pass filter; this infrared image is a stack

of thousands of video frames, digitally aligned and sharpened.)

In this picture, looking at the edge of the visible face of the moon, you can see two parallel

mountain ridges, or rather three — the third one is only visible near the

middle of the picture.

Those are the three ramparts of Mare Orientale.

(In this picture you cannot see the actual Mare surface, but it is sometimes visible from earth.)

To help you get oriented, the red arrow marks the crater Eichstadt and points in

the same direction on both the map and the picture. The big black blob at the top

left of the picture is the crater Grimaldi.

I've done better. I've actually imaged part of the flat central surface of

Mare Orientale, back in 2010.

Permanent link to this entry

|

|

|

This is a private web page,

not hosted or sponsored by the University of Georgia.

Copyright 2018 Michael A. Covington.

Caching by search engines is permitted.

To go to the latest entry every day, bookmark

http://www.covingtoninnovations.com/michael/blog/Default.asp

and if you get the previous month, tell your browser to refresh.

Portrait at top of page by Sharon Covington.

This web site has never collected personal information

and is not affected by GDPR.

Some older pages that contain Google Ads may use cookies to manage the rotation of ads.

No personal information is collected or stored by Covington Innovations, and never has been.

This web site is based and served entirely in the United States.

In compliance with U.S. FTC guidelines,

I am glad to point out that unless explicitly

indicated, I do not receive substantial payments, free merchandise, or other remuneration

for reviewing or mentioning products on this web site.

Any remuneration valued at more than about $10 will always be mentioned here,

and in any case my writing about products and dealers is always truthful.

Reviewed

products are usually things I purchased for my own use, or occasionally items

lent to me briefly by manufacturers and described as such.

I am an Amazon Associate, and almost all of my links to Amazon.com pay me a commission

if you make a purchase. This of course does not determine which items I recommend, since

I can get a commission on anything they sell.

|

|